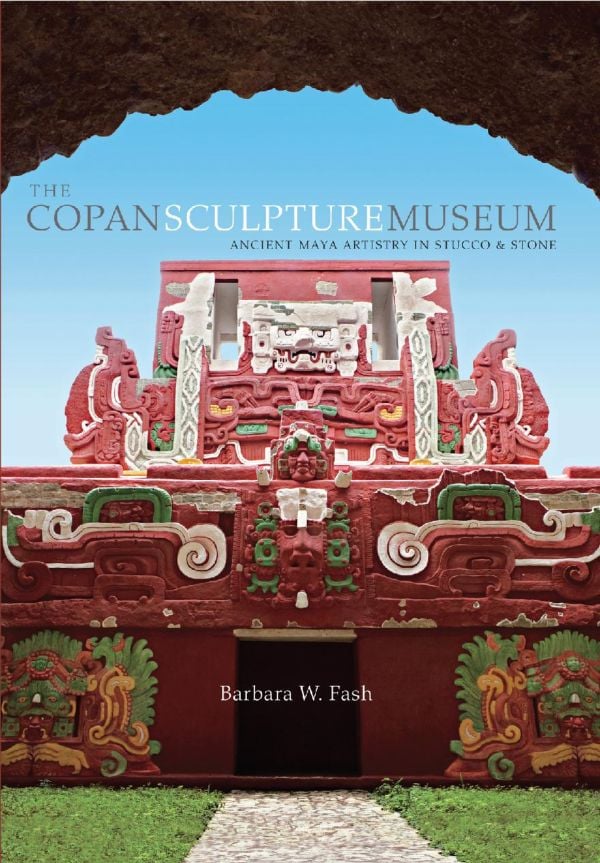

Inaugurated on August 3, 1996, the Copan Sculpture Museum has become a significant feature on the physical and cultural landscape of Honduras.

It presents many magnificent Copan sculptures to the public for the first time, and its reconstructions of building facades allow the mosaic configurations to be viewed nearly as they were seen on the original structures. Each building had a different purpose for the ancient residents of Copan, and as the ruins are pieced back together and studied, the complex fabric of past life in the city is further revealed. The heritage that is being rediscovered brings to the modern people of the area a new sense of identity with and respect for the past. Although traditional Maya culture and languages disappeared from the Copan Valley long ago, their roots can still be detected in the townspeople's daily lives. The residents of Copán Ruinas, who have served the museum as excavators, artists, masons, carpenters, administrators, photographers, and teachers, together with their families, shared in this rediscovery and dedicated their efforts to making the museum possible (200, 201).

In the ancient Mesoamerican world, Copan stood at the forefront in the use of architecture as a means of visual communication. Since the first popular accounts of its stone art and architecture appeared, scholars have debated the meanings and purposes of these masterful artistic expressions. Copan, with its animated imagery, was always considered to display the highest level of achievement in Maya art. Its temples, palaces, and administrative buildings came alive with sculptural decorations that personified the living and supernatural forces inhabiting the Maya world in a way the sculpture of few other cities could rival.

The imagery on Copan's buildings was a form of visual language that conveyed similar conventional meanings to all who viewed it. Unlike the written word, conveyed in hieroglyphs and probably comprehended only by the literate, the large sculptural symbols and motifs on the building facades could be understood by people of all social ranks. In a cosmopolitan city like Copan, the imagery was probably designed to cut across cultural lines as well and to be understood by people who spoke different languages. The wonderfully imaginative Copan sculptors gave material expression to spiritual beliefs and helped spread Copan's religion and art to other areas. In the hands of leaders and groups seeking to mystify and enthrall, the sculpture facades were powerful instruments. Rulers' names, emblems, and sacred place names were emblazoned in iconic form for everyone to see and read.

Now far removed from the seventh and eighth centuries, when most of these works were created, we must look for clues to ambiguous meanings that have been lost with time. Our ideas about the sculptures' messages change as we learn more through excavation and analysis, which is why it is usually necessary to present possibilities in conditional terms rather than offer statements as facts. To understand the complex religious concepts reflected in the sculptural images, it is useful to grasp the idea of personification. As Bill and I wrote in a 1996 article on visual communication in Classic Maya architecture, personification is the notion that everything one experiences has a spiritual personality that can be visualized and represented. The ancient Maya saw water, for example, as a living force that took many forms. Its visual representation as liquid from a mountain spring or lake (often in the form of a serpent with water-lily attributes) differed from its depiction as rain (a Chahk mask), dew (beads), or vapor (scrolls). Maize, in its many cycles and stages of development, also took many guises, from seed (k'an cross), to sprout (curling vegetation), corncob (maize deity), and drying stalk.

The sculpture of Copan offers many vivid examples of the concept that supernatural forces reside in the everyday world. The waterbird from the Híjole structure, which may once have adorned Structure 22 (see chapter 6), is perhaps the most masterful one extant in carved stone. The Rosalila temple (chapter 3) is certainly a magnificent and well-preserved example that, when reconstructed in the museum, allows modern viewers to feel and contemplate the effect such a building had on people who stood before it on the ancient Copan Acropolis. The museum reconstructions help visitors envision the pageantry and the public and private rituals that took place against these symbolically charged backdrops in the city core and in outlying residences alike.

Political messages and symbols that struck a unifying chord in the community, such as the woven mat motif decorating Structure 22A, would have been easily identifiable by anyone who viewed the buildings from the plazas below. Although we can only hypothesize about who attended events in the Principal Group, I have proposed that different social groups participated in events in the center in calendrically timed rounds. In time, powerful groups in the outlying residences created their own animated façades for local enhancement and enjoyment.

Copan's unusually prolific sculptors and masons no doubt played a direct role in this development. As their skill and numbers increased, so, it seems, did the desire to build bolder residences to complement or rival those at the center. Public architectural projects most likely attracted laborers from smaller chiefdoms or other political units, workers who hoped to improve their quality of life by attaching themselves to a wealthy polity. Attracting and training masons and sculptors generated greater power for the ruling dynasty by creating a permanent, skilled workforce for public projects undertaken in the Principal Group. Studying the connection between political status, social power, and architecture, Bill and I have proposed that Copan sculptors and masons formed a special, elite interest group beginning in the Early Classic period, with the founding of the polity. By the Late Classic period, this group would have wielded significant economic power.

In the Copan Valley, 14 residential groups are known to have displayed sculptural façades, and four groups have yielded hieroglyphic benches inside buildings. These finds draw our attention to the economic consequences of architectural construction and its sculptural embellishment. In the Late Classic period, commoners made up an estimated 85 percent of the households in the valley, and elites, 15 percent. Less than 1 percent of the total populace consisted of the actual ruler's household. Scholars estimate that it would have taken 30 workers approximately one year to build the residential Structure 9N-82, and two years for 50 workers to build the larger Structure 22 on the Acropolis (203). The essential point is that architecture is a valuable artifact that reflects social power relations.

Buildings within roughly a half-mile radius of Copan's urban core and in the more rural parts of the valley, such as at Rastrojón just to the northeast of the Principal Group and at Río Amarillo farther to the east, display a wide array of styles and messages in their façade sculptures. Few of them have yet been completely excavated or reconstructed, but on the basis of their sculptural themes and the sites' divergent histories, we can predict that their social and political standings varied significantly as well.

We are still a long way from understanding the internal power politics behind the collapse of royal authority in ancient Copan, but continued investigation of residences and urban structures holds great promise for helping us understand the roles various actors played in producing status and power in Copan. The buildings and their sculptured decorations undoubtedly reflect the inexorable process by which regal order devolved into political chaos and the end of divine rule.

The study of Copan's sculpture is endless, for new interpretations can arise with every new piece unearthed. For example, we are only beginning to understand the meaning and use of color on the sculptures. Advanced technology that allows us to see microscopic remains of pigments in the stucco and stone pores - traces invisible to the naked eye - promises to open a new world of insights into this fascinating subject. Three-dimensional records are being created that offer new means of preserving information and reconstructing fallen façades. Yet despite these new advances, we must continue to preserve the originals, for nothing surpasses the genuine artifact as a means of experiencing and studying the past through our own visual senses.

The Copan Sculpture Museum, however, is important to its community and its nation in ways that reach far beyond its aesthetic appeal and its wealth of information about the ancient Maya. At the museum's groundbreaking, Honduran President Rafael Leonardo Callejas proclaimed it the first cultural monument of the nation that served to foster a national identity. For the Copan community and those of us who worked on the project, it represents more than an affiliation with the Maya past; it represents what a hybrid cultural community - native people, ladinos, and foreigners - could accomplish together by appreciating and preserving an important legacy. As an educational tool, the museum helps thousands of schoolchildren learn about the ancient Maya and become more culturally conscious. It is intended to strengthen respect for indigenous artistic achievements and to be a catalyst for equality and justice for native people in the future.

People of Maya descent are far from the only Honduran citizens to possess native ancestry.Indeed, Honduras has substantially more non-Maya indigenous people, such as the Lenca, than Maya descendants, but their cultures and histories tend to be marginalized in the media and in textbooks in favor of Maya heritage. The Copan Sculpture Museum encourages other indigenous groups in the country to rally support for promoting their rich cultural heritages instead of setting the Maya in competition with them. This is beginning to happen, and new museums and cultural centers are springing up in other areas. One example is Casa Galeano, a history museum and cultural center in Gracias, Honduras, that features Lenca traditions (204).

Today in Honduras, historians such as former Honduran Minister of Culture Rodolfo Pastor Fasquelle and Darío Euraque, a previous director of IHAH, are attempting to balance the cultural identities of Honduras by investigating the overemphasis on Maya heritage that often dominates public attention. Euraque and Pastor have both commented on the way non-native political leaders go to the extreme of characterizing themselves as "Maya" by employing ancient Maya icons and rituals in public events, including the creation of elaborate backdrops featuring Maya symbols for use during presidential inaugurations. Copan, the largest and most heavily visited Maya site in Honduras, lies at the center of this discussion. Without careful thought, efforts to popularize the Maya could eventually erase actual history. Although it was natural to create a museum at the most dynamic, world-renowned archaeological site in Honduras, in choosing the name for the Copan Sculpture Museum, Bill and I spoke out against including the word "Maya." We and some colleagues saw it as exploiting an ancient cultural affiliation that did not represent the ethnic diversity of Honduras as a whole or even of ancient Copan, which, in its Classic period heyday, was a cosmopolitan city that housed enclaves of people from throughout Mesoamerica.

Museums such as the Copan Sculpture Museum offer tangible benefits along with the fostering of ethnic and national identity. Developing nations of the twenty-first century must find ways to keep their people employed and to better educate them. From the inception of government-funded archaeological projects in Honduras, foreign researchers have trained Honduran nationals in all aspects of archaeological work, building a cadre of professionals who lend continuity to the archaeological investigations, maintain the ruins, run the museums, and conduct independent research. Besides creating jobs, the construction and operation of a museum can prompt municipal improvements and generate revenue from tourism.

In Copán Ruinas, residents embraced the idea of the sculpture museum and the goal of using national and foreign aid for a purpose that would benefit the community for years to come. The economic effect was plainly visible as Copanecos improved their homes and installed public facilities such as a new secondary school. Many more children in Copán Ruinas now attend school beyond sixth grade than was formerly the case. Older children no longer leave the town in large numbers but instead find jobs in the town's growing economy. New hotels and restaurants offer a variety of accommodations for travelers and provide employment for residents. These changes, acting to keep families together, have helped strengthen family ties, the backbone of contemporary ladino societies.

The Copan Sculpture Museum brought together a diverse group of government officials, townspeople, professionals, and academics to create a new cultural resource that evokes pride in everyone who contributed. Copanecos' investment in the museum, combined with its economic benefits, should sustain local interest in the museum and preservation of the Copan ruins well into the future. Additionally, the town has established long-term connections with external institutions that will continue to support the museum and provide intercultural and professional exchanges. Reciprocity is already evident through the exchange of replicas and joint conferences, training events, symposia, and university courses between the Copan Sculpture Museum and Harvard University.

The exceptional sculptured façades of ancient Copan, now properly displayed in the Copan Sculpture Museum, contribute to Mesoamerican art, religion, and history appreciated by indigenous descendants, other Honduran nationals, and foreigners alike. Everyone involved in the sculpture museum hopes that this renewed appreciation will inspire people to preserve and study this priceless legacy for future generations.