The Maya today, like people in many other cultures around the world, revere their ancestors.

The ancient Maya believed their male rulers became apotheosized as the sun deity, and female rulers, as the moon deity. They held rituals to honor them at death, and they constructed massive funerary buildings and inscribed monuments to commemorate their reigns. At Copan, the founder of the royal dynasty, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', was the most important ancestor, and archaeologists have found several important structures and carved monuments dedicated to him. So central are they to understanding ancient Copan that the grandest of these commemorative monuments, the Rosalila temple and Altar Q, are presented as the first exhibitions visitors see in the museum (38).

K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' established a royal line at Copan in A.D. 426 and reigned until 437. He was not the first person to rule over Copan; hieroglyphic texts mention even earlier rulers. But he is the pivotal figure whom the surviving historical records carved in stone claim as the founder of the Classic period dynasty. The 15 succeeding rulers all counted their numbered positions in reference to him. Archaeologists believe they have found the burial and tomb of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' in one of the earliest buildings on the Acropolis, nicknamed "Hunal." Bone chemistry analysis indicates that K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' grew up in the central Maya area, and a hieroglyphic text pinpoints the site as Caracol, Belize. Altar Q records that later in life he traveled to central Mexico to receive his authority to rule, most likely from officials at Teotihuacan, the great city that was the central Mexican capital, and then made his way to Copan (39). A different posthumous monument at Copan makes reference to his performing a ceremony in A.D. 416, so it is possible that he came to Copan even before his trip to Teotihuacan.

EXHIBIT 1

The Rosalila Temple

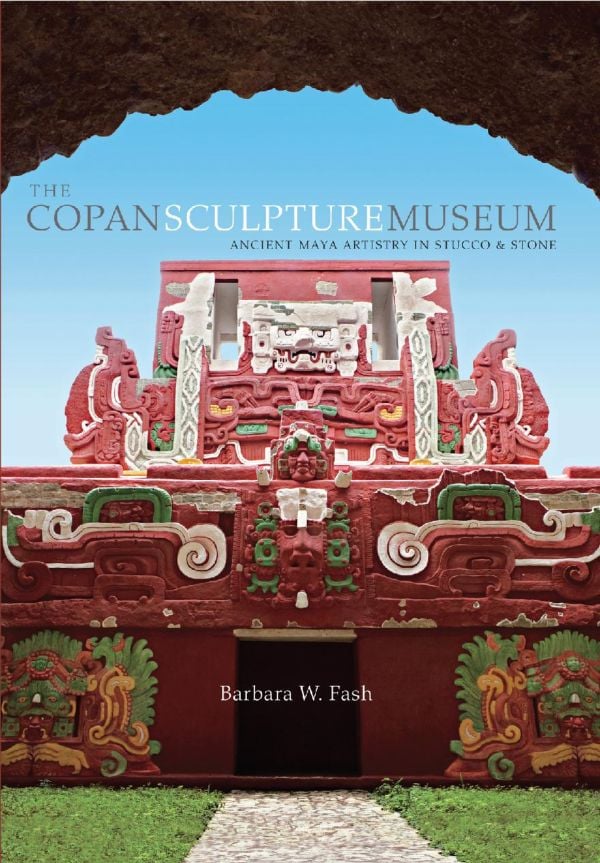

The magnificent temple discovered during tunnel excavations at the site and nicknamed Rosalila was chosen to be replicated as the centerpiece of the Copan Sculpture Museum. Brilliantly painted in red, yellow, green, and white, the building greets awed visitors as they enter the museum, just as the original must once have done in the ancient city. The inhabitants of Copan built the temple to honor K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', whose tomb lay in an earlier building beneath it.

Of all the grand buildings on the Copan Acropolis, only threeStructures 11, 16, and 26-are known to have antecedents dating back to the beginning of the dynastic rule. Later rulers respected the location of each building as, over time, they had masons raise subsequent edifices, one on top of another, in the same spots. Eventually, neighboring buildings filled in the spaces between the original ones. From Gustav Strømsvik's probes in the 1930s, later generations of archaeologists could see that an intricate sequence of buildings spanning the history of the Copan kingdom lay beneath the site surface.

In 1989, Bill Fash, who was already directing excavations beneath Structure 26 and its Hieroglyphic Stairway, asked Ricardo Agurcia to direct new excavations at Structure 16, the highest structure on the Acropolis, as part of the Proyecto Arqueológico Acrópolis Copán (PAAC) (40). Part of this new investigation involved digging tunnels into the interior of Structure 16. As a result, we now understand that a sequence of superimposed buildings ending with Structure 16 was constructed over the tomb of the dynastic founder, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. His tomb, discovered by Robert Sharer and colleagues while digging the earliest and lowest levels of the Acropolis, lies inside a structure named Hunal, at the start of the sequence (41). To Copan's inhabitants this became perhaps the city's most sacred location, at the heart of the Acropolis. Several other of the early buildings that followed in the sequence called Yehnal, Margarita, and Rosalila were decorated with the founder's motifs in painted modeled stucco. Because they are in fragile condition, these decorations can be displayed in the museum only as replicas. Yehnal and Margarita were not fully revealed until after the Copan Sculpture Museum was designed, and it is hoped that replicas of them, too, will be made and displayed in the future.

The most remarkable architecture to emerge from the excavations beneath Structure 16 was the intact Early Classic temple that Ricardo named Rosalila. Throughout Mesoamerica, people's customary pattern of construction was to build up pyramids in stages, or layers, so that to archaeologists they resemble onions with layers to be peeled off. At Copan, ancient masons usually partially demolished an old building, filled it in with the debris, and then constructed a new building over and beyond the ruins of the previous foundation. Rosalila, however, was special: it was deliberately "entombed" inside the next structure in the sequence. No other building has been found so carefully preserved below the surface of the Acropolis or anywhere else in Copan. Rather than demolish the building, the ancient Maya whitewashed it with a thick coat of stucco and then surrounded it with a layer of packed clay before the next phase of construction. They buried nearly the entire structure intact, including its roof crest, an architectural feature never before seen preserved at Copan.

Apparently they also conducted elaborate "termination" rituals at Rosalila. Among other things, they placed a special offering in the temple's central chamber-nine "eccentric flints" wrapped in blue cloth and cached near the front doorway (42). Flint objects found at many Maya sites were knapped into intricate abstract figures and shapes, which earns them archaeologists' designation as "eccentric." Copan's eccentric flints often took the form of sacred lance points with numerous profile heads. Clearly, this termination offering and the careful burial of the external decoration signals that the Rosalila temple was a sacred structure honoring the memory of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and his tomb. The ancient inhabitants could not bear to see it destroyed, so they buried and preserved it with the utmost care.

Ricardo and his assistants excavated Rosalila until 1996, meticulously uncovering the fragile stucco designs that embellished the structure. They employed conservation measures such as injecting fissures and separations with a lime solution and applying a mixed lime and consolidant paste to seal and reinforce broken edges, to ensure that the decorations deteriorated no further. Working closely with the draftsmen who recorded the exposed areas in detail, I compiled the drawing segments into a composite image in order to complete the reconstruction of Rosalila's façade that is presented as the museum's centerpiece. This work guided the excavations, and because identical designs were repeated on multiple sides of the building, in many cases Ricardo and I jointly deemed only minimal uncovering of the fragile stucco to be necessary.

The color scheme of Rosalila's plaster decoration was ascertained slowly over time. Initially, stucco technician Fidencio Rivera and I conducted micro-probes beneath the surface of the thick termination layer of stucco, using the soft points of wooden and bamboo implements to reveal the details of carving hidden underneath (43, 44). In the upper registers of the temple, the colors were only sparsely preserved, probably because of weathering and intense sunlight. Karl Taube and I later had to examine the stucco painstakingly to find traces of pigment revealing the painting scheme on these levels. By 1995 Ricardo had discovered an unwhitewashed bird motif on the north side of the structure (45). The expansion of an adjacent building in ancient times had covered this portion of the stucco design before the termination coating was applied to the rest of Rosalila. This accident of preservation left the colors clearly visible on the stucco bird, which served as the primary color guide for the bird figures on the lower register of the museum replica.

Many people are curious about how Rosalila got its name. Sadly, we do not know what the ancient Maya called the structure, for its name is unrecorded in the inscriptions that have been found so far at Copan. Before PAAC, archaeologists had given numbers to the buildings they found to distinguish them from one another. Rather than use a cumbersome and potentially misleading numbering system, for PAAC it was decided that pyramidal bases, or substructures, would be given color names, and buildings and temples, or superstructures, would receive bird names. For example, other early Acropolis substructures were called Purpura (purple), Esmeralda (emerald), Yax (blue-green), and Azul (blue). Superstructures included Águila (eagle), Perico (parakeet), and Loro (parrot). Even this system became modified. When the first decorated stucco façade of Rosalila was uncovered, it was assumed to be the façade of a substructure, because no well-preserved temple with stucco decoration had previously been found at Copan. Hence the color designation Rosalila, or rose lilac. If we had a chance to change the temple's designation to a bird name now, perhaps Templo K'uk' Mo' (quetzal macaw) would be more appropriate.

The design of the museum replica was based on the knowledge we had for Rosalila in 1990. Two excavation seasons later, Ricardo penetrated the plaster floor that was in use during the final years of the temple's life and discovered that an elaborately decorated substructure lay buried beneath it. On this substructure, two well preserved masks flanked a grand central staircase leading up to the temple (46). The staircase bore a hieroglyphic inscription dating the 47. Artist's reconstruction of Hunal, Yehnal, Margarita, and Rosalila with its substructure masks and stairway added. structure to the reign of Ruler 9, around A.D. 550. By the time of the new discovery, it was too late to change the design of the Rosalila replica-and if we had added to its height, it would no longer have fit into the museum. In any case, the replica is faithful to what visyears of its life, visitors to the Acropolis saw of Rosalila in the final when the substructure was covered by the plaster floor and no longer visible (47).

To create the Rosalila replica, local artisans Marcelino Valdés and Jacinto Abrego Ramírez first made clay versions of the stucco designs based on scaled enlargements of my reconstruction drawings and the visible stucco originals. For close access to the original, they worked in a specially roofed area on the low, flat expanse on top of Structure 14, directly opposite Structure 16 at the site. Although stone carvers by choice, the two soon came to appreciate and even prefer the versatility of clay for rendering the large, complex designs of the façade (see 14). Before we made latex molds of any section from the clay model, I checked its accuracy by carefully comparing it with photographs and the original stucco. The latex molds, backed by fiberglass resin countermolds, were then cast with reinforced cement and transferred from the work area to the museum site.

Relying on detailed measurements of the original temple, Rudy Larios planned and oversaw the construction of the replica's reinforced interior structure, onto which the cast sections were secured (see 15). On the lower level, the masons were actually able to cast the birds directly onto the structure's support beams and walls. On the upper levels, the slices of cast sculpture sections were painstakingly hoisted onto the building with a cable and secured in place. Each overall section took three to six months to complete, and constructing the entire building was a three-year endeavor. On opening day, the building was vibrant with fresh paint, barely dry.

Rosalila's sculptural message can be understood only in terms of the history of its ancient building site. Excavations have revealed that the temple was built directly above several earlier structures that were also embellished with stucco designs. The three best preserved are known as Margarita, Yehnal, and Hunal, the earliest, which dates to the time of the founder of the dynasty, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. Elaborate royal tombs housed in these earlier structures are believed to be those of the founder himself and a related royal woman, thought to be his wife. Emblazoned on the exteriors of Margarita and Yehnal were colorfully painted emblematic names related to K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and the founding events of his dynasty (48, 49). The same symbolism was carried forward to embellish Rosalila on an even grander scale. It is clear from studies of the art and architecture at Copan that this historical figure, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', became the city's most honored ancestor. His burial at this spot transformed it into a sacred place for all eternity.

Rosalila was one of the last buildings with a stucco façade to be visible on the Copan Acropolis. In the temple's heyday, a courtyard filled with other dazzling, stucco decorated buildings surrounded it. But slowly these buildings were replaced, covered by new temples that had stone rather than modeled stucco sculpture decorating their exterior surfaces. The stones were tenoned into the buildings' façades, and their visible surfaces were carved. They were then coated with a thin whitewash of lime and were painted, producing the same visual effect as the earlier modeled stucco. This shift in technology took place around A.D. 600 and was gradually perfected in the following centuries. Stone sculpture had been in use for the larger free-standing monuments at Copan for centuries, but not until this time did it come into extensive use on building façades. My colleagues and I speculate that the ancient builders tired of the constant maintenance required by the fragile stucco and looked for a more durable substitute. Stone carving provided Copan sculptors with new possibilities for monumentality and symbolic expression on the exteriors of buildings.

Another motivation behind this shift may have been that p preparing the lime for the stucco matrix was costly and time consuming. Limestone had to be quarried and carried from its source, and many trees had to be felled for fuel to heat the limestone during processing. As the landscape became increasingly deforested, stucco preparation became a greater challenge. Although architects continued to use massive amounts of lime stucco for the roofs and floors of their buildings, with the introduction of tenoned stone sculpture they were able to cut back on consumption for the decorated façades.

Even with the advent of the new technology, Rosalila and its neighboring structure, “Ani," were preserved for many years as relics of the older style. As new buildings crept up around them, the two appear to have been tended and revered until the last. Yet in time even these lone stucco survivors on the Acropolis were engulfed by new buildings. Rosalila was eventually covered several times, the final phase of construction taking place during the reign of Ruler 16, Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. Historic buildings succumbing to fresh waves of architectural construction-how often have we seen this happen in our own modern cities?

EXHIBIT 6

Altar Q

In the hieroglyphic inscriptions carved on stone monuments at Copan lies a wealth of information about rulers and events in the life of the city. The single most informative stone is Altar Q, so named by Alfred Maudslay in 1886. This famous, monolithic, square altar honors K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and his dynastic successors, displaying on its sides carvings of all 16 rulers in the Copan dynasty (50).

In the early twentieth century, Herbert Spinden proposed that the altar's inscriptions referred to an astronomical conference and that the seated figures depicted on it were attendees. By the 1970s, epigraphers had begun to understand that the hieroglyphs on the top of the altar recounted historical events involving the Copan dynasty, and the 16 human figures, 4 on each side, composed a chronological list of kings who ruled Copan from A.D. 426 to 775. Beginning with K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', who holds a burning torch, each ruler sits above a name glyph and holds an unlit paper torch in his hand. The fire and torches symbolize the transfer of authority from the ancestral founders of Tollan, the "place of the bulrushes," the mythical origin place for the ancient people of Mesoamerica. Authority over Copan appears to have been conferred upon K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' at Teotihuacan, where sacred "New Fire" ceremonies and the granting of kingship for many Mesoamerican cities is recorded to have taken place for centuries.

Altar Q was erected in A.D. 763, the first year of the reign of Ruler 16, Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. It was set at the base of the grand staircase climbing Structure 16, the central pyramid of Copan's Acropolis and the final building in the sequence covering Rosalila and the founder's funerary temple. In 1996 the altar was transferred to the sculpture museum for preservation and exhibition, and a reproduction was left in its place at the site (51). An earlier plaster cast of the altar, made in 1892 by the Peabody Museum expedition, remains on display in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Altar Q measures 6 feet (1.85 meters) on each side and 4 feet (1.22 meters) high. Originally it sat on four carved cylindrical stone pedestals, but as the centuries passed, the pedestals gave way under the altar's weight. To early visitors such as Juan Galindo in 1834, they appeared to be merely circular stones propping up the altar from the ground. In 1990, Ricardo Agurcia excavated around the altar to find the floor on which it rested and discovered the lower sections of the pedestals. The fallen pieces were painstakingly reassembled by assistant Carlos Jacinto, student and sculptor Barbara Gustafsen, and me, and they are part of the museum exhibit today. Unfortunately, the carvings on the pedestals are mostly eroded beyond recognition. What little can be seen are masks on two of the cylinders and portions of dates on the other two-perhaps the date 6 Kaban 10 Mol, on which the altar was dedicated (see p. 53 for more on the Maya calendar).

In 1999, the founder's tomb and funerary slab, supported by four cylindrical supports, were discovered buried in one of the earliest phases of Structure 16. Altar Q and its bases, dating some 340 years later, could then be understood as a replication of the funerary bed of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. The altar testifies to the strong memory of historic events kept alive by the ancient people of Copan through written records and visual symbols and undoubtedly through spoken histories and legends as well. Placed in front of the pyramid housing the founder's tomb at its core, Altar Q not only paid tribute to K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' but also served to legitimate Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, Ruler 16, within the dynastic line.