Although people are drawn to the grand artistic wonders of Copan's Principal Group, the Copan Valley was an equally fascinating landscape in ancient times, dotted with busy communities and splendidly decorated residences.

Understanding how the ancient polity was held together, as well as the dynamics of power among the nobles and their families, has been a component of research at Copan for decades. Investigations of residential areas such as Las Sepulturas have helped unravel the nature of interactions between the ruling dynasty and the outlying communities. Within the Principal Group itself, the sculptures that once embellished a building called Structure 22A offer further clues to the social and political organization of Copan (169). Its motifs strongly suggest that it served as a community meeting place or council house, perhaps a place where representatives of residential districts met and community festivals took place.

Exhibit 46: Structure 22A

One of Tatiana Proskouriakoff's most valuable contributions to the archaeological study of Copan was the wonderful set of architectural reconstructions she produced for her 1946 book, An Album of Maya Architecture. Her hypothetical reconstruction of Structure 22A, part of a watercolor scene of Copan's East Court, reflects what was known of the building at that time (170). Limited excavations by the Carnegie Institution in the late 1930s had revealed one doorway and an undecorated interior bench with a plain circular pedestal on top. Finding no hieroglyphic inscriptions, the investigators halted. Outside, on the east side of the structure, facing the larger Structure 22, a portion of the façade remained intact. On it could be seen a pattern of simple curving blocks laid at angles to form the design of a woven mat (171). From this example and other similar stones visible on the surface surrounding the building, Proskouriakoff projected the existence of other mat designs around the entire façade. There the matter rested for nearly 50 years until Proskouriakoff's insights once again inspired and guided a new generation of scholars who probed deeper into the ruins of Structure 22A.

Although this building on the Acropolis appeared relatively insignificant next to its larger, more elaborate neighbors, PAAC excavation teams set to work uncovering the remainder of its fallen walls and sculptures in 1988. Early on, I suspected that the building might have been the city's council house, a structure known historically in Yucatán as the popolna, or "mat house," from pop, "mat," and na, "house" (possibly popol otoot in the Chorti Maya of the Copan region). Rulers and noblemen convened in these houses while seated on woven reed mats. Sixteenth and seventeenth-century records such as the Libros del Chilam Balam and the Popol Vuh, colonial Maya accounts of sacred history and religion, tell that among the most common titles for royalty and other nobles were "Lord of the Mat" and "Lord of the Jaguar Mat." The woven mat pattern, or pop, was a symbol of rulership, perhaps referring not only to the mats rulers literally sat upon but also, figuratively, to the interwovenness of the community and to unity among the nobles and rulers.

The historical documentary evidence suggests that council members were chosen from important patrilineages—descent groups traced on the father's side—and held office for specific terms before stepping down. Five years would have been a likely calendrical interval. The colonial sources also reveal that community or council houses were places where the Maya staged public festivals and learned traditional dances. Some living Maya villagers still gather at popolna. Researchers have witnessed town festivals, complete with feasts and dancing, at such buildings in traditional rural communities in Quintana Roo, Mexico.

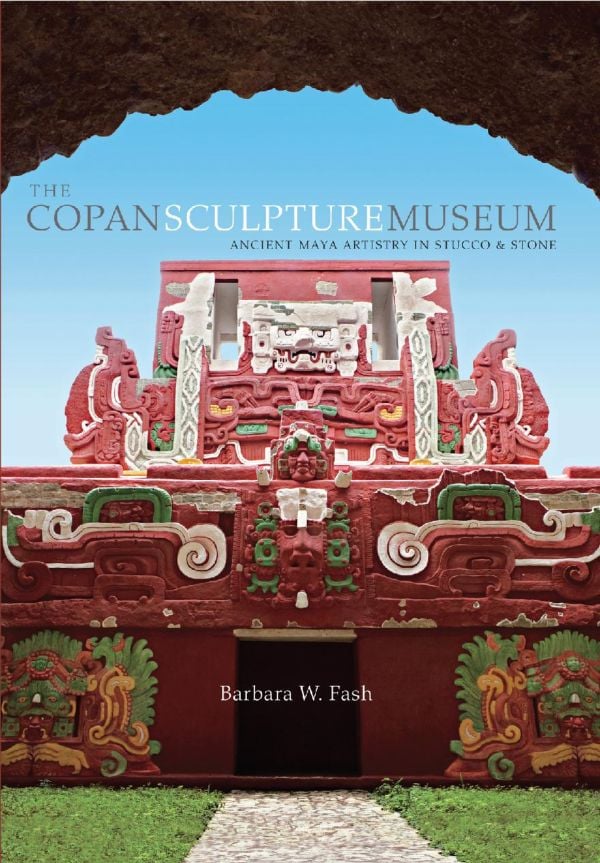

As digging proceeded through the debris of building stones and mortar at Structure 22A, nearly a thousand pieces of sculpted stone were uncovered, many lying exactly where they had fallen in antiquity. From their positions, the architectural and sculptural elements of all four sides of the building could be reconstructed on paper. It became clear that this small edifice had been an elegant one. Eventually we were able to reconstruct its front, south-facing façade as exhibit 46 in the Copan Sculpture Museum (172).

Structure 22A had an open front with three large entranceways, as would have been appropriate for a building with a public function. The knotted or woven matlike design, the building's most prominent decorative motif, was repeated three times on the front and back façades and twice on the short sides, for 10 examples in all. Its iconic significance was no doubt easily apparent to ancient Maya people of all ranks. Perhaps they were also able to interpret a hieroglyphic motif that includes the elements for sak nik, or "white flower," which was repeated around the cornice. Sak nik te'il na was another name for the community house in some Mayan dictionaries. We reconstructed several ornamental motifs on the building's cornice that seem to represent this concept. An ajaw face possibly symbolizing the nik flower is framed by two upright serpent stamens paired with circular elements representing the sak sign. The na, or "house," signs beneath the seated figures slightly lower on the building.

Paired above each interwoven motif on the north, south, and west façades were two hieroglyphic signs (16 in all), each composed of the bar and dot numeral representing the number nine attached to an ajaw day sign, the first day of the Calendar Round (173). This intentional pairing might indicate that the glyph had a double meaning. It seems to have marked the Calendar Round date falling on the day 9 Ajaw, and it also marked the building as a "nine ajaw" house, or "House of Nine Lords," possibly referring to nine councilors. Correspondingly, nine niches appear to have been placed around the façade, each containing a human figure seated above a large hieroglyph probably denoting a place name. I think these nine figures (or nine lords), each with a distinctive headdress and necklace or pectoral insignia, might represent the council representatives from various areas around Copan. Such a position existed among the Yucatec Maya in the sixteenth century; it was called holpop (hol, "head," pop, "mat"), or "he at the head of the mat." Alternatively, the figures might not be actual portraits of representatives but rather a merging of ancestral and patron figures whom the council members embodied. Further study might reveal that the figures also have a connection with the bolon tz'akab, or "Nine Lords of the Night," who, according to ancient Maya belief, ruled the nocturnal landscape.

My colleagues and I believe we have identified the actual residential location associated with one of the place names on this building. The name over the pillar between the left and middle front doorways was represented by a glyph in the form of a fish. While excavating a royal family residence south of the Acropolis in the 1990s, Will Andrews and his team discovered a series of similar fish sculptures fallen from the façades. One had even been ritually buried as the major feature of a subfloor cache. This evidence supports the idea that the royal residential complex was known by this fish name, perhaps "cai nal". Possibly the fish glyph on Structure 22A referred to the same residential complex, and the figure above it, to that area's representative at community council gatherings (174).

The 9 Ajaw glyphs on Structure 22A alone provide too little calendrical information to identify the year the building was dedicated. But the event would typically have been held at the end of a 5-, 10-, or 20-year cycle in the Maya calendar. Only three dates in the Late Classic period fit this cycle and fell on the day 9 Ajaw; they were in the years A.D. 682, 746, and 810. Judging from the archaeological stratigraphy of the neighboring Structures 22 and 26, together with David Stuart's decipherment of a dedication date of A.D. 715 for Structure 22, the first possibility is unquestionably too early. The sculptural style and other architectural details of Structure 22A, when compared with those of other, dated buildings at Copan, make the third date extremely unlikely as well. Therefore, both the archaeology and the epigraphy point to June 12, 746, as the most likely dedication date.

From just outside Structure 22A comes additional evidence that supports the interpretation of a public function for this building. In front of it stood a platform (numbered Structure 25 on maps) that measured 26 by 98 feet (8 by 30 meters) and was found to have been replastered several times, probably to keep its surface smooth. There is no evidence that it had a superstructure. Bill and I suggest that this raised surface was a dance platform used during performances and festivals. Two upright, grinning jaguars adorn the sides of the platform, and to me they appear to be in a dance pose, inviting the viewer to join in (175). Karl Taube suggests that the jaguars are iconic name glyphs for Ruler 7, Bahlam Nehn, or "Mirror Jaguar," whose burial was found many layers beneath this platform. A large deposit of refuse found just off the southwest corner of Structure 22A contained pottery, stone tools used to process meat, charcoal fragments, ash, and stone burners or containers, all of which appear to represent the remains of ritual feasting.

If Structure 22A indeed functioned as a popolna, then it broadens the political and administrative model for ancient Copan. Rather than the ruler acting alone, it would appear that by at least the time of Ruler 14, a council of representatives from the valley settlements was an essential part of the scene. My sense is that the representatives and the places they hailed from were tied into the Maya worldview through mythological place names and images of the supernatural patrons of those places.

Recently, other scholars have built on this interpretation from somewhat different viewpoints. Elizabeth Wagner's idea is that the mats decorating Structure 22A actually represent knots in nine sections that relate the place names and figures on the building to the bolon tz'akab, a name for the Nine Lords of the Night. Another idea is that the sak nik element on the building's cornice represents the expiring breath of dead ancestors, suggesting that the ruler constructed the building to honor nine deceased lords and supernatural deities. The "nine lords" concept is still little understood, but it is possible that people affiliated themselves and their social units with them as mythological or spiritual entities and locations. In any case, comprehending the full meaning of Structure 22A in ancient times can help in understanding residential settlement patterns and the distinctiveness of the building's functions and purposes. Certainly, researchers' ideas will continue to evolve as they learn more about ancient Maya political structure.