The histories of Mesoamerican peoples, like those of most peoples everywhere, are partly histories of warfare.

The Mayan-speaking groups were no exception. Maya rulers launched raids or all-out battles against their neighbors and sometimes fought prolonged wars against rival kingdoms. They fought to acquire new land, force others to pay tribute to them, or fulfill ritual pacts made with supernatural forces. Often rulers started battles in order to secure captives. Although the Maya usually offered animals in sacrifice to the supernatural forces, some important rituals at urban centers also required the sacrifice of war captives. Preserved ancient carvings and paintings of battle scenes reveal that Maya warfare involved a great deal of pageantry and commotion. Banners and war standards evoked the mythical animal patron deities that accompanied warriors into battle for strength and protection. Warfare was often timed according to auspicious calendar dates or the movements of celestial bodies. Archaeological evidence suggests that warfare intensified as the authority and power of the Classic Maya ruling elites eroded and kingdoms increasingly competed over resources.

At Copan, evidence for warfare and its associated rituals comes from the iconography on several buildings and stelae. Rulers were depicted as robust warriors brandishing shields, lances, sacrificial implements, and ropes with which to tie captives. Their roles as powerful war captains became more important as outside forces pressured the stability of the Copan polity and as the need to carry out rituals in order to triumph over misfortunes increased. Rulers from neighboring areas threatened to overtake Copan and topple its ruling dynasty, while population increases prompted environmental catastrophes such as deforestation and the spread of diseases.

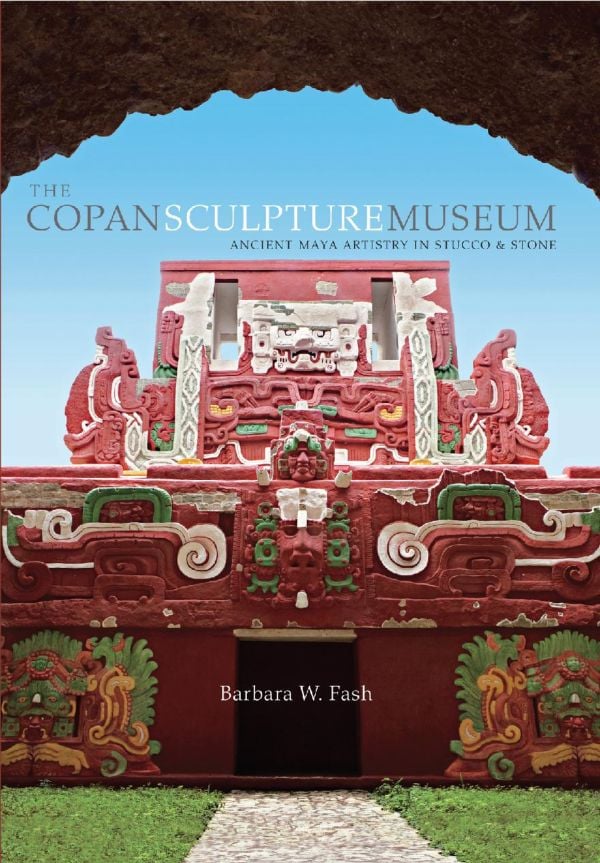

Nowhere at Copan is the theme of warfare and war-related ritual inscribed more prominently in architectural sculpture than on Structure 26, the pyramid famous for the immense Hieroglyphic Stairway on its west side (122). Exhibit 30 in the Copan Sculpture Museum displays a stela discovered inside the structure called "Papagayo," buried beneath the Structure 26 pyramid. Exhibits 31-33 display motifs and inscriptions from the façades of the temple that once crowned the pyramid. Before turning to those sculptures, however, it is useful to know something of the history of Structure 26, its famous stairway, and archaeologists' exploration of them.

Alfred Maudslay was the first explorer to call attention to the Hieroglyphic Stairway, investigate the mound, and give the stairway the name by which it is still known today. John Owens conducted the first clearing and excavation of Structure 26 in 1891-93 as part of Harvard University's Peabody Museum expedition. After Owens died of a tropical fever and was buried in front of Stela D in the Great Plaza, his field assistant and subsequent director of the expedition, George Byron Gordon, carried on the work (123). Gordon was responsible for the initial reordering of the fallen steps of the stairway and the carvings of seated warrior figures that punctuate its ascent. He and others took photographs, which are archived at the Peabody Museum, and made molds of many of the carved risers. The photographs remain a trove of information, retaining details of the hieroglyphs now too eroded to make out. The Peabody Museum published Gordon's complete study of the Hieroglyphic Stairway in 1902, and his reconstructions and decipherments of the key dates in its text have withstood the test of time.

When the Carnegie expedition started fieldwork at Copan, its participants devoted much of their time to restoring the monuments and architecture. At the insistence of epigrapher Sylvanus Morley, one of the first buildings the team worked on was Structure 26. Members of the earlier Peabody expeditions had found the majority of blocks from the stairway dislodged and fallen out of position after centuries of plant growth, earthquakes, and rainstorms. The Carnegie team restored the two sections of steps that had remained in sequence together (see 27). Subsequently, in the 1940s, Carnegie project members filled in the unrestored spaces with the remaining hieroglyphic blocks and seated figures. They added sequences of cal 123. Excavation of the Hieroglyphic Stairway by the Peabody Museum in 1895 revealed only calendrical dates, which were the only parts decipherable at the time, but made a jumble of the remaining blocks of the inscription.

In all, 63 steps and a decorative balustrade were reconstructed on the west side of the pyramid, and these are what visitors see today. In 1986, a sixty-fourth step was uncovered at the base of the stairway; it had been covered over when the plaster floor was refurbished in ancient times, probably to keep water from collecting at the base. Epigraphers have spent years studying the inscriptions carved into the steps, deciphering and reconstructing the many passages of the text in efforts to reconstruct its original order and message. Today they have succeeded in reconstructing 71 percent of the text.

The inscription presents an exceptional public record of local dynastic history, giving accounts of the lives and accessions of Copan Rulers 7–15, in effect to legitimate their places in the ruling dynasty. Significantly, although the founder of the Copan dynasty, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', is named in several places in the inscription, the stairway particularly highlights the long reign of Ruler 12, K'ahk' Uti' Ha' K'awiil. Just as the tomb of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' lies beneath Structure 16, so the tomb of Ruler 12 lies at the heart of Structure 26, associated with an earlier building (124). Ruler 12's 67-year reign (A. D. 628-95) corresponded to the reigns of other powerful Maya rulers, such as K'inich Janahb' Pakal of Palenque and Itzamnah B'ahlam I of Yaxchilan. He consolidated power in the kingdom and ushered in the cultural florescence known throughout the Maya area as the Classic period.

Scholars believe that Copan's rulers built the Hieroglyphic Stairway in two stages. Ruler 13, Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil, sponsored the first stage on Esmeralda, three years into his reign, as a dedication to Ruler 12, which covered his earlier burial structure and ancestor shrine. Following the death of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil at the hands of a ruler of Quirigua and the subsequent short reign of Ruler 14, their successor, K'ahk' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil, Ruler 15, rebuilt the stairway and temple. The final dedication date of the relocated stairway, its addition, and the entire final-phase pyramid is 9. 16. 4. 1. 0, or May 8, 755. Another important event recorded in the lengthy stairway text was a conflict with the neighboring city of Quirigua, which ended with the fateful capture and decapitation of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil, Ruler 13. It seems that Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil began the stairway to honor his father, Ruler 12, and K'ahk' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil finished it essentially as a monument proclaiming the accomplishments of Copan's royal lineage and reaffirming its dynastic honor and warrior strength following Ruler 13's defeat. This would explain why portraits of the rulers as powerful warriors grace the central axis of the stairs and the temple's exterior façade (125).

Exhibit 31: Structure 26, Hieroglyphic Panel

The temple atop Structure 26 continued the war-related imagery established on the Hieroglyphic Stairway. The temple was in complete ruin long before archaeologists rediscovered it in the late 1800s. Members of the nineteenth-century Peabody expedition collected large quantities of scattered sculpture from the exterior façade and interior hieroglyphic inscriptions from the fallen walls. Some 25 blocks containing portions of a lively hieroglyphic text from the temple's inner room made their way to the Peabody Museum, whose contract with the Honduran government-written more than 100 years ago-stated that the museum could remove half of what it found. Another 20 blocks or so were taken to the Honduran National Museum in Tegucigalpa. During the Carnegie Institution's excavations in the 1930s, additional glyph blocks from the same panel inscription were found as workers cleared the structure for restoration. Morley cataloged and photographed the pieces and made the first attempt to reconstruct their order (126).

Later excavations of the terraces on the north and east sides of Structure 26 in 1986, by Bill Fash and other members of the Hieroglyphic Stairway Project, uncovered even more temple inscription blocks (127). Finally, in the 1990s, the Tegucigalpa pieces were brought to the lab at the Centro Regional de Investigaciones Arqueológicas (CRIA) and reunited with the Copan sections to prepare for their eventual reassembly in the Copan Sculpture Museum (128). David Stuart and I then reassembled a majority of the blocks in the sandbox, leaving spaces for the absent Peabody blocks. In 1996, I worked with conservation personnel at the Peabody to make paper molds of the inscription blocks in its collection. Transported to Copan, the molds were cast in plaster and rejoined with the rest of the inscription for the first time since the blocks fell from their positions on the temple walls. Finally, Stuart and I oversaw the reconstruction of this extraordinary hieroglyphic text in the museum (129, 130). We are still on the lookout for some of the missing pieces to fill in the gaps.

The temple's inscription actually forms the body of a two-headed beast with birdlike attributes, including talons at the top of each side (131). The entire form stretches across an expanse that we reconstructed as a solid panel, although conceivably it was a deeper niche with a wooden lintel. The text focuses on Rulers 11-15, with the accession date of Ruler 12 singled out for special recognition. This is not surprising, because his tomb was found in an earlier temple construction beneath Structure 26, and the grand Hieroglyphic Stairway was dedicated to him.

The inscription is most remarkable for being written in a unique double script. David Stuart first noted this intriguing feature when he realized that each phrase and ruler's name in Mayan glyphs in the inscription was mimicked by a glyph with Teotihuacan elements (132). The sets of glyphs appear in paired columns, with the central Mexican sign always on the left and the Classic Maya glyph on the right. The glyphs with Mexican attributes are so far unique to the Copan inscriptions.

They imply that the sculptor was making reference to the distant and by then abandoned city of Teotihuacan and possibly to Copan's earlier associations with that great center. This is particularly informative because of the paucity of glyphs from Teotihuacan and scholars' poor understanding of them. Although the glyphs are not direct representations of Teotihuacan writing, the coupling of a Teotihuacan "font" with deciphered Mayan glyphs opens up possibilities for new decipherments of the earlier Teotihuacan writing system. Perhaps the foreign glyphs were an attempt to represent the secret, esoteric Zuyua language, which the Maya considered to be associated with Tollan, the mythical place of origin for ancient Mesoamerican cultures.

The text also harks back to the pilgrimage K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' made to Teotihuacan's origin house, the Wite'naah, to be invested with the office of king. The inscription claims illustrious descent from the founder for the entire dynastic succession of rulers. Because Teotihuacan was a great metropolis of far-reaching influence associated with warrior-merchants, Ruler 15's decoration of Structure 26 and the Hieroglyphic Stairway with Teotihuacan warrior imagery, in addition to the dual-script temple inscription, honors a distinguished line of rulers as warriors empowered by the legacy of this powerful city in the wake of the death of Ruler 13.

Exhibits 32 & 33: Structure 26, Temple Masks and Façade Sculptures

Documentation and analysis of the mosaic sculpture fragments associated with the temple on Structure 26 began in 1986 as part of the Hieroglyphic Stairway Project. During excavations, I helped reassemble motifs from the scattered piles of sculpture that matched fragments emerging from the ground (133). This exercise revealed that some of the same iconographic themes found on the balustrade and seated figures of the Hieroglyphic Stairway were repeated in the temple's façade sculptures and roof comb. As on other Copan structures, the main theme was ancestor veneration, with ancestral rulers shown in the guise of warriors.

High on the temple's roof comb, six seated warriors were repeated around the building (134). Their warrior costumes resemble those of the seated figures on the Hieroglyphic Stairway, and at one time they brandished shields and lances. Their attire includes elements of the Tlaloc warrior costume such as the interlocked year sign and supernatural owls in their headdresses and distinctive leg garters with trapezoidal elements.

Six war serpent masks with proboscis-like lancet tongues formed niches along the molding of the temple's upper register. Along the sides of the war serpents' mouths, stylized butterfly wings were appended to droopy-lidded, starry eyes (135). These might have represented the warrior's soul, which in ancient central Mexican belief was transformed into a butterfly at death (136). Similar examples are found in painted Mexican codices showing star eyes along a celestial band, possibly another symbol for the warrior's soul.

The themes of warfare and sacrifice that predominate on this temple represent a departure from the sustenance themes portrayed on embellished façades of many earlier buildings at Copan. This shift may reflect the general atmosphere in the war-torn Maya lowlands of the Late Classic period and in Copan particularly following the death of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil. After his defeat by the Quirigua ruler, the surviving nobles might have felt it necessary to make a strong political statement to exalt the ruling dynasty. The sculptural message on the temple was meant to instill confidence in the rulers' supernatural abilities and warrior skills.