Copan, the southernmost city of the ancient Maya world, rose to power in a fertile valley carved out by the Copan River, surrounded by verdant mountains rising to about 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) above sea level (20).

The city's residents enjoyed a subtropical climate with an average yearly temperature of 78 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Centigrade) and two marked seasons―a dry one from December to May and a wet one from May through November. Like their counterparts throughout the Maya area, which stretched as far north as the Yucatan Peninsula and west to the Pacific Ocean, the people of Copan interacted with members of neighboring Mesoamerican cultures, especially those of central and southwestern Mexico and El Salvador (21). They also allied, traded, and intermarried with people from other Maya cities, such as Calakmul, Palenque, and Tikal, all of which are mentioned in inscriptions on monuments at Copan. Archaeologists find that Maya urban centers often reflect their cosmopolitanism with trade goods from many places, written scripts in a mixture of languages, and distinctive blends of architectural and art styles.

What made the ancient Maya remarkable were their highly developed writing, art, urban planning, astronomy, and monumental architecture. Today, more than 6 million people speaking 26 surviving Mayan languages reside in the same area as their ancestors. Scholars believe that Mayan languages shared a common proto-Mayan ancestor around 2000 B.C., from which branches emerged as groups broke off to settle new areas. Copan was part of the Chol-speaking region. Chorti is still spoken in Maya settlements along the Guatemala-Honduras border and is slowly moving back into Honduras.

When the Spaniards arrived and conquered the Maya regions, between 1524 and 1697, they faced many independently ruled kingdoms that fought hard to hold onto their way of life. The Spaniards introduced the Roman Catholic religion, alphabetic writing, and many new diseases during their subjugation of the Maya people. Despite it all, the Maya survived and today carry on many of their ancient traditions, often blended with modern ones. Although Maya hieroglyphic writing and many other practices were lost, the people's distinct identity endured. Revivals of languages, culture, and history in the last century testify to the Maya's beliefs and determination.

The Copan Valley is covered with the ruins of ancient households, often clustered around reliable water sources. Archaeologists completed a survey of the valley in 1980 and mapped more than 3,400 visible house remains, or mounds (see inside front cover). Excavations suggest that at least as many more buildings lie invisible beneath the surface, bringing the total count closer to 6,000 dwellings. Some of these ruins date as far back as 1400 B.C., during the Preclassic period (1800 B.C.-A.D.200), when small groups of people settled the valley.

Quarry Hill is a rock outcrop that served as one of the sources of the volcanic tuff used by the people of Copan to construct their buildings and monuments. The valley was settled by 24 horticulturists who farmed and performed religious rituals in sacred caves in the nearby mountains. The population grew significantly until the end of the Classic period (AD 250-900), when the ruling dynasty collapsed, leading to a decline in population due to disease, natural disasters, political unrest, warfare, and environmental degradation. In the sixteenth century, Spanish conquistadors invaded the valley and found only a handful of people remaining. The modern village of Copán Ruinas was founded in 1870 and named "San José de Copán" after its patron saint. It is located less than a mile (1.5 kilometers) west of the Principal Group ruins. The village was built over an ancient ruin that was still visible in 1935. Copán Ruinas has grown considerably since the mid-twentieth century and is now home to over 6,000 people. Government projects in 1979 made water and electricity available to everyone living in the town proper, and the old dirt road to Copán Ruinas was paved in 1980. Hotels, restaurants, and souvenir shops are now available for visitors, and public education was expanded through the high school level in 1995.

To the north of the Principal Group lies an outcrop of volcanic tuff, which was the source of the stone used by the ancient people of Copan to construct their buildings and monuments. The valley began to take shape geologically from 134 million to 64 million years ago through the deposition of limestones and siltstones. Later, volcanic explosions deposited tuff, a powdery ash that solidifies into porous rock, in thick layers over the valley. The Copan River and its tributaries carved courses through both the tuff layers and the limestone beds, depositing soil and building river terraces and alluvial fans as they traveled. The remains of the oldest houses indicate that early farmers settled in the valley, drawn by the fertile soils in which they grew maize and other staples. As the population grew and a complex Maya culture arose, people found the tuff ideal for buildings and sculptures. All but one sculpture exhibited in the Copan Sculpture Museum was carved from this local volcanic tuff. Other quarries of the same stone are still used today for construction in Copán Ruinas and the surrounding area.

The ancient Maya sculptors did not have metal tools, and their main carving implements were hard greenstone celts, tools shaped like chisels or axe heads, in a variety of sizes. For finer incising, their tool kit contained sharpened bones and chert and obsidian points. The greenstone, or jadeite, was probably imported from a source in the Motagua Valley, about three days' walk to the east, and obsidian was brought from an outcrop at Ixtepeque in what is today Guatemala, some 50 miles (80 kilometers) away. Chert was mostly mined locally, but some came from sources traced to modern-day Belize.

The Copan that visitors see today is vastly different from the Copan experienced by early foreign visitors to the valley. In the sixteenth century, the valley was covered in subtropical forest, and spider monkeys swung in the trees. Wild peccaries roamed the foothills, macaws squawked overhead, and deer abounded. The first written account of the archaeological site came from Diego García de Palacio in 1576, who wrote to King Phillip II of Spain. He described the stelae of the Great Plaza, which were still standing, and the sculptures on building façades, which had not yet collapsed. He reported that the village near the ruins was called Copan, and the ruins have been called by that name ever since.It is possible that the name derived from that of the native chief Copan Galel, who valiantly defended the district against Spanish invaders in 1530.

The ruins were all but forgotten for the next 250 years until, in 1834, the government of Guatemala sent an archaeological expedition to Copan under the direction of Colonel Juan Galindo. Galindo, who had excavated at other Maya ruins such as Palenque in Mexico, drew public attention to the ruins through books published in London, Paris, and New York. He wrote and drew at Copan for several months and excavated a tomb chamber in the East Court that contained pottery vessels and human bones. Four years later, the famous U.S. diplomat and explorer John Lloyd Stephens, accompanied by the English artist Frederick Catherwood, embarked on a Central American journey that began with a lengthy stay in Copan. The two chronicled their travels in the well-known book Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. Stephens's lively account and Catherwood's magnificent illustrations awakened Western interest in all of Central America, especially Copan (24).

The Englishman Alfred Percival Maudslay undertook the next significant exploration of Copan, in 1885. Traveling on his own, Maudslay conducted the first scientific excavations and recording of monuments at Copan, the results of which were published in London in 1889-1902 in the six volumes of his work Archaeology in the series Biologia Centrali-Americana. Maudslay was the first to describe the Maya corbelled vault, to create a nomenclature for the monuments and buildings (for example, Stela A and Altar Q), to take extensive photographs at the site, and to supervise the making of drawings and plaster casts of stelae and altars. The six archaeology volumes contain his detailed descriptions and sharp photographs along with superb drawings by artists Annie Hunter and Edwin Lambert. These depictions are treasured today, together with the 185 casts, because many Copan monuments have suffered erosion in the past century. Maudslay's maps and descriptions of Temples 20 and 21 are the only reliable records researchers have of these buildings and their sculpture, for both buildings washed into the Copan River in the early 1900s. Maudslay transported the plaster casts and a substantial inventory of Copan sculptures, including the carved figural and hieroglyphic step from Temple 11, to the British Museum, where they remain today.

With an edict from the Honduran President, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University undertook expeditions in 1891-95 and 1900, focusing its efforts on Copan's Acropolis. The Peabody's work was important for the discovery of nine stelae and the excavation of the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Structure 26, whose glyphs compose the longest pre-Columbian text known in the Americas. The museum's teams also worked on the Reviewing Stand of Temple 11 in the West Court, on some East Court buildings, and at the royal residential area south of the Acropolis, known as El Cementerio because of the many burials unearthed there. Marshall Saville led the first of the four Peabody expeditions, in 1891–92 (25). John Owens, the second expedition director, fell ill with a tropical fever and died in Copan in 1893. He was buried in front of Stela D in the Great Plaza, where a weathered plaque now marks his grave. Alfred Maudslay was persuaded to head the excavations in 1893–94 and was followed by Owens's assistant, George Byron Gordon, who later published The Hieroglyphic Stairway, Ruins of Copán. Gordon also explored the caves north of the village along a stream known as Quebrada Sesesmil. As part of its contract with the Honduran government of the time, the Peabody Museum obtained a collection of more than 600 casts of Copan sculptures and approximately 300 pieces of original sculpture, including a seated figure and 15 random glyph blocks from the Hieroglyphic Stairway.

Early in the twentieth century, several scholars made important contributions to our knowledge of Copan. Herbert J. Spinden wrote "A History of Maya Art: Its Subject Matter and Historical Development," a complete analysis of the style, content, and meaning of Maya art, using copious examples from Copan. American scholar Sylvanus G. Morley made many visits to Copan between 1910 and 1919. He took hieroglyphic decipherment to new levels in his massive 1920 book "The Inscriptions at Copán" by calculating the dates of all the known monuments. Morley's personality and enthusiasm endeared him to the townspeople of Copán Ruinas and to the Honduran government. His resourcefulness and diplomacy enabled the Carnegie Institution of Washington, which hired him as field director for its Central American Expedition in 1915, to carry out an extensive archaeological study at Copan in conjunction with the Honduran government. The amicable and capable Morley, who participated in Carnegie projects until 1946, set the tone and the standards for foreign collaboration with Central Americans in future scientific endeavors.

During the later Carnegie years at Copan, 1935-46, after a lapse in fieldwork following World War I, a new team of workers restored many of the buildings and monuments of the Principal Group, including Ballcourt A, Temple 11, the temple at the top of Structure 22, the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Structure 26, and the stelae of the Great Plaza. Gustav Strømsvik, field director for the Carnegie's later expeditions to Copan and a legendary figure in Copán Ruinas known locally as "don Gustavo," directed or personally carried out the great majority of this reconstruction work. He also used his practical engineering skills to oversee the building of the archaeology museum and fountain on the village square in Copán Ruinas, and he supervised the rechanneling of the Copan River away from the Acropolis, where it had caused severe damage.

Morley, working more in Yucatán at this point, also arranged for the Carnegie team to hire the accomplished architect Tatiana Proskouriakoff to execute reconstruction drawings of the architecture of Copan and other Maya sites. Proskouriakoff had graduated from Pennsylvania State University and caught Morley's attention while she worked for a University of Pennsylvania expedition. Her beautiful watercolors of Copan, now at the Peabody Museum, are frequently reproduced and admired for their accurate and insightful glimpses into a grand ancient city (30). Proskouriakoff's keen observation of the abundant fallen sculptures around Copan allowed her to produce some remarkable reconstruction drawings that reincorporated the fallen blocks into the once-existing façades. Her pioneering work formed the foundation upon which the ongoing Copan Mosaics Project and the Copan Sculpture Museum were built.

In 1952, the government of Honduras took steps to establish the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (IHAH) under the direction of Jesús Núñez Chinchilla (31). He continued the restoration work in the Principal Group and conducted excavations in the valley. Núñez Chinchilla had received training while working with archaeologist John Longyear, a staff member on the Carnegie expedition, excavating and sorting ceramics from ruins in the vicinity of the Principal Group. In his thorough study "Copán Ceramics" (1952), Longyear published the first detailed map of the ruins and house mounds in the valley, made by surveyor John Burgh. Under Núñez Chinchilla, IHAH set about to preserve as many loose sculptures as possible by bringing them to the Copan Regional Museum of Archaeology at Copán Ruinas and to a small storage room at the entrance to the ruins. Although the exact provenances of most of these pieces have been lost over the years, the sculptures were saved from disappearing forever into looters' hands. In 1971, IHAH built a fence to delimit the perimeters of the site core and to enclose and protect the Principal Group. The new fence was erected atop the foundations of a stone wall the Peabody expedition had constructed in 1895 to keep out cattle.

In the mid-1970s, another sequence of investigations commenced that has continued without pause to the present. At that time, José Adán Cueva, a Copaneco who had worked with Morley as a young man and whose father had assisted the earlier Peabody expeditions, directed IHAH (32). He proposed that the Honduran government fund investigations in Copan, and he invited Gordon R. Willey, Bowditch Professor of Central American Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, to design a long-term program of research and preservation (33). Willey conferred with colleagues William R. Coe and Robert J. Sharer, of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, before initiating an archaeological survey of the Copan Valley and preparing recommendations for future work.

Over the next three years, 1974-77, Willey directed a multidisciplinary project that focused on the residential areas in the valley around the Principal Group. Extensive mapping and household excavations by Willey and his students Richard Leventhal and William Fash (Bill) revealed new evidence about ancient Maya settlement patterns and socioeconomic history. The team combined this evidence with new data from geographers and geologists who worked at reconstructing the valley's ancient environment and agricultural history. Longyear's ceramic studies were updated, and Willey published the new studies in "Ceramics and Artifacts from Excavations in the Copán Residential Zone." Bill, then a doctoral student at Harvard, wrote his dissertation about ancient Copan's rise to statehood. He arranged for me to come to Copan in 1977 to draw artifacts for the Harvard project. That year, the excavations brought to light a hieroglyphic bench, which I had the privilege of drawing, and it set our future endeavors in motion.

This phase of Harvard research ended in the summer of 1977, and later that year the Honduran government began funding the Proyecto Arqueológico Copán (PAC). Claude F. Baudez, of the French Centre National de Recherche Scientifique, directed the first phase, PAC I (34). An international group of archaeologists and staff members completed and published Harvard's valley map, test-excavated habitation areas all across the valley, continued the ecological studies, renewed excavations in the Principal Group, resumed hieroglyphic and iconographic studies of the monuments, initiated a catalogue system for the loose sculpture, and constructed a modern archaeological research facility. Additionally, PAC I workers and researchers began to investigate the earlier levels of construction buried beneath the Acropolis and carried out the first scientific mapping of the constructions exposed where the Copan River had cut through the ruins. The results of this ambitious project were published in 1983 in the three volumes of Introducción a la arqueología de Copán, Honduras, edited by Baudez. Continuing from the Harvard work as head project artist, I drew many stelae and the Hieroglyphic Stairway for studies of the sculpture and inscriptions under the supervision of Baudez, Marie-France Fauvet-Berthelot, and Berthold Reise. Monument recording continued through the second phase of the project, PAC II, and many of our sculpture drawings were published in Baudez's book Maya Sculpture of Copan: The Iconography.

PAC II began in late 1980 under the direction of William T. Sanders of Pennsylvania State University and kept its momentum for four more years. Sanders was especially interested in the economic and political growth of ancient Copan, so he directed extensive excavations in Las Sepulturas, the residential area east of the Principal Group (35). Although many of the ruins there dated to the Late Classic (A.D. 600-900) and "collapse" periods at Copan, the area also has dwellings dating back to Preclassic times, before A.D. 400. This research helped scholars reconstruct the domestic daily life of ancient Copan. The PAC II publications included the three-volume Excavaciones en el área urbana de Copán, edited by Sanders, and The House of the Bacabs, Copan, Honduras, edited by David Webster.

One of the large Late Classic structures excavated by Sanders's team, Structure 9N-82, revealed a fallen sculpture façade and hieroglyphic bench, which was unexpected at a residential group that distance from the main center. Bill excavated much of the fallen sculpture at the rear of the structure, and together we studied the sculpture from all sides in 1982–83. This led us to consult with Rudy Larios, who was responsible for the architectural restoration of Group 9N-8, of which this structure was a central part (36). As a result, some of the mosaic sculpture blocks were restored to their original positions on the front of the building. This work led directly to the formation of the Copan Mosaics Project, launched by Bill and me in 1985, which was conceived to preserve and study the façade sculpture from buildings throughout the Principal Group and the Copan Valley (37).

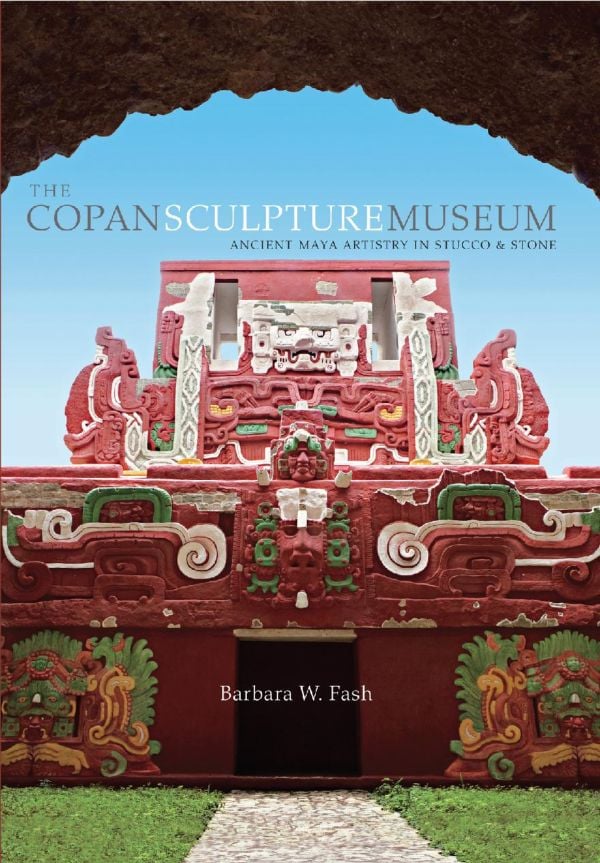

Together with the Copan Mosaics Project, excavations at the Principal Group and into the heart of the Acropolis have been the primary research undertaken at Copan in recent decades. In 1986 Bill secured funding through the National Science Foundation, Northern Illinois University (where he taught and led summer field schools for 7 years), USAID, IHAH, and other granting institutions to pursue the conservation and investigation of the Acropolis on a massive scale. He directed several contiguous projects that grew into the Proyecto Arqueológico Acrópolis Copán, or PAAC. PAAC incorporated several major subprojects headed by co-directors from Honduras, Guatemala, the University of Pennsylvania, and Tulane University. Building on the PAC II work in Las Sepulturas, Pennsylvania State University independently ran several seasons of excavations at Group 8N-11 in the early 1990s, for which I supervised the sculpture Since the conclusion of PAAC in 1995 and the inauguration program. of the Copan Sculpture Museum in 1996, Penn State investigators have continued to work on independent projects in the region and publish their findings. Bill and I, now returned to Harvard University, have run 11 more years of summer field schools at Copan, and Ricardo Agurcia devotes his time to research on Structure 16 in addition to directing the Asociación Copán.

In recent years IHAH has continued important conservation efforts at the Principal Group and salvage operations at ruins affected by modern construction in the Copan Valley. Although much is left to be discovered and understood about ancient Copan in the years ahead, the Copan Sculpture Museum underscores the importance of doing so responsibly, in conjunction with the conservation and careful management of Copan's scientifically and artistically priceless buildings, artifacts, and sculptures.