The Copan Sculpture Museum features the extraordinary stone carvings of the ancient Maya city known as Copan, which flourished on the banks of the Copan River in what is now western Honduras from about 1400 B.C. until sometime in the ninth century A.D.

The city's sculptors produced some of the finest and most animated buildings and temples in the Maya area, in addition to stunning monolithic statues (stelae) and altars. Opened on August 3, 1996, the museum was initiated as an international collaboration to preserve Copan's original stone monuments. Today it fosters cultural understanding and promotes Hondurans' identity with the past. The ruins of Copan were named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980, and today more than 150,000 national and international tourists visit the ancient city every year. In addition to the Copan Sculpture Museum, the town of Copán Ruinas hosts the Copan Regional Museum of Archaeology, established in 1939.

The Copan Sculpture Museum

Copan is justly famous for its intricate high-relief stelae and altars, which are unsurpassed at any other site in Mesoamerica. But its freestanding monuments and architectural sculptures, carved from soft, porous local volcanic tuff, have suffered exposure for centuries to sun, wind, rain, and temperature changes, resulting in flaking, erosion, and loss of details or whole sections of carving. The Copan Sculpture Museum offers a means of conserving many of these vulnerable stone sculptures. Some of the monumental stelae and altars are now protected and exhibited inside the museum, along with lively sculptural façades that archaeologists excavated and reconstructed from jumbled piles of stone fallen from temples at the ruins. The exhibits represent the best-known examples of building façades and sculptural achievements from the ancient kingdom of Copan, now available to the public for the first time in more than a thousand years.

Architecture and its sculpture were inseparable to the ancient Maya. Like their counterparts in many other early cultures, including those of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Southeast Asia, Maya rulers and architects planned and constructed temples and their supporting structures as microcosms of their worldview. Often they embedded calendrical and astronomical information in the alignments and proportions of these important structures. Vibrant sculptures decorating the outside walls further illustrated Maya concepts of the world and their place in it. In their most divine aspects, the major temples represented sacred mountains, nexuses from which godlike rulers could traverse paths to supernatural realms, communicate with their ancestors, and influence the forces of nature. Some were funerary temples, honoring important rulers and ancestors. The freestanding monuments, or stelae, were erected to record historical information about the rulers while emphasizing the celestial importance of commemorated events such as births, accessions, calendrical cycles, marriages, warfare, and deaths.

One of the beauties of the Copan Sculpture Museum is that it is an on-site museum, keeping the preserved art as close as possible to its original context. Visitors to the archaeological site of Copan retain fresh images of the ruins and their surroundings as they contemplate the sculptures and buildings reconstructed inside the museum. The museum's proximity to the ruins also reduced the complicated logistics and risks that would have arisen in moving immense sculptures over greater distances. Because the museum is situated on a former airstrip cleared in the mid-twentieth century, no danger existed of further destroying major archaeological remains in its construction.

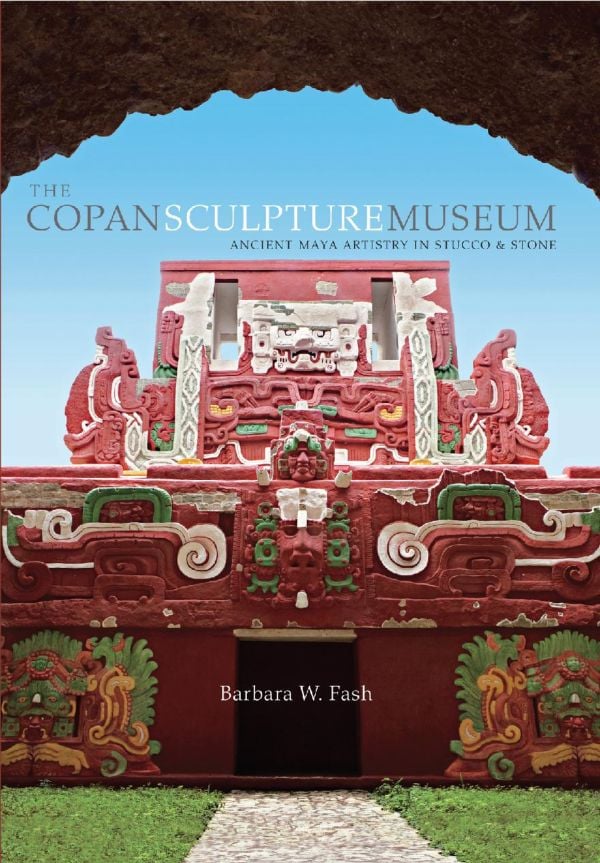

During the planning of the sculpture museum in 1990, it was recognized that the building would become an imposing addition to the Copan archaeological zone. The design team did not want the structure to overwhelm the ruins themselves. With the ancient Maya worldview in mind, the profile of the 45,000-square-foot museum was kept as low as possible, and its lower level was designed in the form of an earthen platform or "mound" like the remains of ancient edifices all over the Copan Valley. Trees hide the exterior, and the entrance is the stylized mouth of a mythical serpent, symbolizing a portal from this world to the past world of the Maya.

The entrance leads dramatically into a serpentine tunnel passageway that symbolically transports museum visitors to another place and time. It was also designed to give visitors the feeling of passing through the tunnels that archaeologists dig to reveal the earlier constructions buried inside later buildings. The tunnel's darkness and curves, interrupted only by soft illumination, resemble the mythical snake; the humid soil smells like the underground excavations.

Finally, the silent tunnel opens suddenly onto a breathtaking vista - the museum's centerpiece, a magnificent, brilliantly colored sixth-century A.D. temple replicated in its entirety. This is "Rosalila," so named by Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle, the Honduran archaeologist who discovered this masterpiece of Copan artistry. It is the most intact building uncovered at the site to date, and its facsimile adorns the center of the museum, surrounded by companion monuments. In its role as the sacred mountain, Rosalila rises from the underworld (the museum's first floor) through the middle world (the second floor) and reaches toward the celestial realm. The sculpture themes on each floor of the museum are organized to reflect these three levels of Maya cosmology. The building's accent colors reinforce the cosmological sense, with dark earth colors on the lower level, and on the second level, red to symbolize the blood of life.

The museum is a four-sided building oriented to the cardinal points. It reflects the fact that the four directions and the sun's yearly path are fundamental aspects of the Maya world. Four is also the number associated with the Maya sun god and the parameters of a cornfield, or milpa, the foundation of settled village life in Mesoamerica.

Natural light has illuminated the monuments and buildings of Copan for centuries, so every attempt was made to use natural light in the museum without sacrificing preservation. Skylights and a compluvium - an opening at the center of the roof that admits light and rain - allow the sun, in its yearly movements, to highlight some exhibits more than others at certain times or on certain days of the year, just as it does at the archaeological site.

In the words of Angela Stassano, the museum's architect: "Everything [in the museum] has a supernatural quality; it becomes a blend between the past, present, and future. Inside, the ramp with its stylized skyband and the museum itself grow upward to the sky. It has a movement of vertical ascension. There is no other museum like it; that is the heart of its beauty. This was our offering to our culture and to the world. The majority of museums try to stand out, to impose themselves, but not this one; this one attempts to appear invisible and humble, just showing the beauty and glory of our past and ancestors."

Creating the Copan Sculpture Museum was an extraordinary project that involved many people from all walks of life, people who shared a vision and forged strong bonds in making it happen. At the highest levels, the museum was a collaboration between the Presidency of the Republic of Honduras, the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History, or IHAH), the nonprofit Asociación Copán, and a U.S.-based project funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The building is an original design by Honduran architect Angela M. Stassano R., working in collaboration with Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle, William L. Fash (my husband, hereafter referred to as "Bill"), the architectural restorer C. Rudy Larios, and me.

Before the three years it took to design and build the museum, from 1993 to 1996, came years of investigation into Copan's sculpture by a huge team of students, professional colleagues, and volunteers working on projects that Bill and I co-directed. In 1984, after the two of us had enjoyed some success piecing together the sculpture fallen from the façade of a building known as 9N-82C, or the Scribe's Palace (later restored by Rudy Larios), we began going to the ruins on weekends with some of our co-workers to probe the sculpture piles for motifs we could recognize and reassemble. The following year we proposed what we called the Copan Mosaics Project as a rescue operation to support IHAH in conserving and analyzing the sculptures that were deteriorating in these piles at the ruins. We started the project by cataloguing and studying the sculptures associated with Copan's ballcourt.

In 1988 we broadened the scope of the mosaics project, and it became one branch of a research and excavation project for the entire Copan Acropolis, the huge mass of superimposed buildings at the core of the ancient city. This endeavor was called the Proyecto Arque ológico Acrópolis Copan (Copan Acropolis Archaeological Project, or PAAC), Rudy Larios came on board with the project, directing all aspects of restoration operations. Linda Schele and David Stuart, both att historians and epigraphers-scholars who study ancient inscriptions also joined the project and transformed our under- standing of the recorded history of the ancient city, the lives and times of the rulers, and the iconography of the sculptural monu- ments. The Copan Mosaics Project is ongoing today, dedicated to the study and conservation of the tens of thousands of sculpted stone blocks that once adorned the building façades of Copan. My role has been that of project co-director, artist, and sculpture co-coordinator, supervising the cataloguing and contributing to the interpretive analysis of more than 28,000 component pieces of sculpture.

The museum project began as a joint effort between Hill and me and our closest colleague, archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia, oxucutivo director of the Asociación Copan and twice director of IHAH. The idea for a museum to preserve and display the sculpture of Copan germinated in our conversations after work during the Copan Acropolis Archaeological Project, often as we watched sunsets over the valley. In 1990 Ricardo and Bill founded the Asociación Copan, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the Copan ruins and disseminating the results of investigations at the site. Through the Asociación, Ricardo hired architect Angela Stansano, who had recently renovated the anthropology museum in San Pedro Sula. Honduras, to design the building. Starting in 1991, Ricardo, Bill, and 1, along with our talented friend and colleague Rudy Larios of Guatemala, who served as PAAC's restoration director, met with Angela many times to lay out the core ideas for the museum and int tiate the design concept Angela and I conferred about everything from overall layout to details of iron grille decoration. The two of us even set about the ruins to measure the façades of the buildings we wanted to reconstruct inside, and Angela served as a human scale in our photographs (7)

The museum would never have materialized without the vision and support of two Honduran presidents, Rafael Leonardo Callejas and Carlos Roberto Reina. President Callejas, a staunch supporter of preservation of the ruins and the cultural heritage of Honduras, visited Copan only four weeks after he was inaugurated in 1990, and we soon pitched our idea to him in the capital. He quickly gave us his wholehearted approval to move ahead with the plans and generously committed U.S.$1 million to the construction of the building from his presidential funds.

Once the museum plans were finalized, it took over a year to line up a construction firm, and we watched our plans stall in the mire of government bureaucracy. To jump-start the process, Ricardo made a case for administering the presidential construction fund through the Asociación Copán rather than the central government. When this was approved, construction surged ahead. But because of the late start, the museum was not finished during Callejas's term, and it fell to President Reina's administration to complete and inaugurate the museum. Reina gave his full support to the project, saw to its com- pletion, and presided over a grand-opening ceremony and celebra- tion in August 1996. Today a bronze plaque at the entrance to the museum heralds the contributions of both presidents, who have become icons for their respective political parties (see pp.172-173).

By the time we began the museum project, Bill was already an accomplished archaeologist and project director, a successful grant writer, and a seasoned navigator of bureaucracy. While he wrote letters and proposals and gave tours and public lectures, Ricardo made the 14-hour round-trip drive to the capital, Tegucigalpa, almost weekly, carrying paperwork from one government office to the next. He met with construction firms, engineers, and local officials while untangling bureaucratic snags. Quite the dynamic duo, they each had a special charm that won the trust and confidence of both the Honduran and U.S. government officials they engaged along the way. In the end, the construction contract was awarded to Pedro Pineda Cobos, with Raul Wélchez V., an engineer from Copán Ruinas, as project manager. Ground was broken at last in 1993.

Besides the Presidency of the Republic of Honduras and the Asociación Copán, the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia played a vital role in making the museum a reality. The project would not have survived for long without IHAH's Copan regional director, Oscar Cruz Melgar, who was on hand locally to coordinate the IHAH components of the project. "Profe," as he was known-short for profesor had been with IHAH since 1976 and had long championed the study of Copan's sculpture. As the museum construction progressed, Profe arranged meetings, loaned vehicles, sent people on supply missions to San Pedro Sula, and facilitated the transfer of sculpture between the ruins and the museum site, always with a calm, steady hand and prudent advice.

Long before the museum building was completed, our team began planning and preparing its exhibits. Indeed, the genesis of many of them, like the genesis of the museum itself, lay well back in the Copan Mosaics Project. At the start of that project, piles of loose sculpture-jumbled pieces that had tumbled from the ancient buildings over the centuries-dotted the open spaces and temple staircases around the ruins (8). We gave numbers to these heaps and, together with Honduran staff, university students, and Earthwatch volunteers, sorted and catalogued many of them.

In time we were able to distinguish repetitive designs, motifs, and styles, which gave us insights into the themes illustrated on different buildings. Understanding those themes in turn helped us reassign countless stray sculptures to specific buildings of ancient Copan.

Much of the detective work involved excavating previously untouched portions of the structures, which allowed us to match pieces of sculpture that we knew came from a certain building with loose pieces found in the confused surface piles. What had seemed to be a giant jigsaw puzzle (without a box-top guide) proved to be a window onto the artistic masterpieces commissioned by Copan's rulers to showcase their power and impress the city's growing population.

Bill, Ricardo, Rudy, and I wished for these varied and meaningful mosaic sculptures to be reassembled, displayed, and appreciated for centuries to come. As professionals, we follow the international treaty dating to 1964 known as the Venice Charter, which lays out strict reconstruction codes that prohibit overrestoration of original buildings at archaeological sites. IHAH and all other parties engaged in scientific research at Copan abide by these codes, restoring only walls that are found intact. So until the idea of the sculpture museum emerged, it appeared that the once glorious, now fallen temple facades would be forever hidden away in storage areas.Fortunately, international standards do allow for didactic reconstructions in museums, away from the existing archaeological remains.

Since 1977, it had always been part of Copan archaeology projects to incorporate and train Hondurans, especially "Copanecos," as people from Copan refer to themselves, in skills needed to work at the ruins. Once the museum was underway, several key Copaneco staff members shared responsibility with me for the exhibit installations at the Copan Sculpture Museum. Foreman and chief enthusiast was Juan Ramón ("Moncho") Guerra, whose Herculean efforts routinely made the impossible possible. We had no high-tech equipment, so Moncho's ingenuity and improvisations with an old winch and pulley system were vital as he supervised the cushioning and moving of all the sculpture, facing stones, and several-ton stelae by dump truck into the completed museum building. Using humor to energize the workforce, he oversaw the setting up of equipment and scaffolding, the building of the foundation for the Rosalila replica, and the hoisting of cast sections of Rosalila into position.

Meanwhile, Copanecos Santos Vásquez Rosa and Francisco ("Pancho") Canán, archaeological excavators and veterans of the Copan Mosaics Project, used their expertise in masonry and the recognition of sculpture motifs to reassemble the pieces of the building façades we chose to exhibit. Years earlier, Santos and Pancho had heaved and carefully placed all the catalogued sculpture into safe storage at the Centro Regional de Investigaciones Arqueológicas (CRIA) under Bill's and my supervision. Now, as they worked on each exhibit, we moved all the pertinent sculpture for it into the museum, organized by catalogue number to coincide with my key plans. I worked side by side with them when I could, but as a mother of three, with a job at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, I had to travel to and from Boston every two months for two-week stints once the exhibit installation was in full swing. Before departing for Boston, I would leave Santos and Pancho my detailed drawings, plans, and photographs. They used these as guides to raise the complete façades. Each time I reappeared, we pored over the reconstructions, often taking some parts down and reassembling them to make minute corrections in structural details that we had not anticipated when the pieces were on the ground. We often spent hours searching for just the right size facing stone to fill in a gap or developing the perfect mortar mix.

In the end, the three of us, aided by Bill and Rudy at crucial moments, were able to reconstruct the original sculptures for seven complete façades, combining them with faced stones also excavated from the original structures. Still, the reconstructions are meant to be seen as works in progress. We used the structural and iconographic clues available to us at the time to reconstruct the façades to the best of our ability, but we expect that new information will come to light that will advance our interpretations and alter some of the reconstructions now exhibited. For this reason, we built all the exhibits using a reversible earth, sand, and lime mortar. This will enable future researchers to change or add sculptures to the exhibited façades in the event that new information or more pieces become available.

In a very few instances, we made replicas of sculptures and used them in reconstructions to complement existing motifs or to present a more comprehensive example of a particular image.For example, at Copan's Structure 32, only one human portrait head was found during PAAC excavations in 1990, although the bodies of six human stone figures were uncovered. The other five carved heads had already disappeared in antiquity. To enhance the overall presentation in the museum, we made a replica of the one extant head and installed it with one of the figures in the exhibition. In other instances, we used information from identical motifs on a building to reconstruct parts of severely broken sculptures. An example is the reconstruction of the tips of the macaw beaks in the ballcourt façade.

The single greatest challenge in preparing the museum's exhibits was creating the complete replica of the ancient temple called Rosalila. There, the team benefited from the experience and expertise brought by Rudy Larios, who designed and supervised the building of Rosalila's foundation structure. With his wife, Leti, he also trained staff and oversaw the molding and replication of many of the other monuments now on exhibit (11). Rudy's countless talents and boundless energy made everyone believe that things never before attempted could be done. His cheers of "Fabuloso!" still ring in the museum halls.

To replicate in clay the stucco designs decorating the original façades of the Rosalila temple, we began with my composite scale drawings, which were derived from accurate technical drawings of exposed sections done by José Humberto ("Chepe") Espinoza, Fernando López, and Jorge Ramos. Chepe had been drawing and carving wooden sculpture replicas before I ever arrived in Copan. Working on many archaeological projects over the years, he had mastered the illustration of ceramics and other artifacts and trained younger artists to work alongside him. Fernando, a skilled topographer, brought a keen spatial understanding of the construction phases of the buried architecture that we were about to reproduce. Jorge had started as a young archaeologist's assistant, excavating with Ricardo Agurcia, and went on to earn a Ph.D. at the University of California, Riverside, in 2006. As of 2007, he was back in Copan, co-directing a project with Bill and me that would teach yet another generation of Copanecos about sculpture analysis and conservation.

Working from my drawings, stone carvers Marcelino Valdés (12) and Jacinto Abrego Ramírez (13), both superb artists, set out to model Rosalila's spectacular façades in clay. From the clay models, which I checked to maintain accuracy, they made molds that were later cast in reinforced concrete sections. Working as a team, it took us three years to complete the job. I remember how, when the first façade bird was finished, we sat down and revised our calculations of how long it would take to complete the entire structure. We all chuckled in disbelief at what we faced. But despite relentlessly sore backs and the plague of hungry mosquitoes, Marcelino and Jacinto had the time of their lives reproducing that amazing work of art (14).

With the concrete façade replicas at last completed, Moncho Guerra had each section hoisted by rope onto the fortress-like framework designed by Rudy Larios and Fernando López. Moncho saw to it that the sections were seamlessly joined in their proper positions, no easy feat on the highest parts of the building (15).

The ancient Maya painted their buildings in brilliant colors, and we wanted to replicate the colors as precisely as possible on the reproduction of Rosalila. We needed a paint that would not peel and would resemble the original paint. Finding it was no easy task. Luckily, a chain of helpful referrals led us finally to the Keim Company of Germany, which produces a special mineral paint frequently used in outdoor conservation.When mixed with a silicate solution, the paint petrifies with the cement matrix to which it is applied, creating a long-lasting adhesion that resists the growth of mold and mildew for years. Obtaining the paint, shipped from its American distributor, was not easy either. It required many long-distance telephone calls, faxes, and e-mails on both ends to track down shipments and negotiate their release through Honduran customs agents. Meanwhile, our colleague Karl Taube, an anthropology professor at the University of California at Riverside, spent hours crawling about the Rosalila tunnels in 1996 to help unravel the complexities of the temple's elaborate color scheme. The vibrant colors seen on the replica today are a direct result of his Sherlock Holmesian efforts.

The Keim Company's paints promised to hold up on some stelae and architectural replicas made for outdoor placement as well. During the museum planning, IHAH sought to bring some original monumental sculptures, still in place at the site, indoors to ensure their long-term preservation. Eight were chosen for display in the museum: Stelae A, P, and 2, Altar Q, the doorway of Structure 22, the skulls on Structure 16, a ballcourt bird-head marker, and the lower niches from Structure 9N-82. The replica team cast copies of them in cement reinforced with iron rods and painted them in colors as close to the original as possible. Signs identify the replicas, which were erected in place of the originals among the Copan ruins, where visitors see them today.

The installation of the exhibits in the sculpture museum took four years to complete. But besides them, the museum building itself needed appropriate architectural accents and finishing touches. In an effort to respect the ancient motifs and not add modern ones, we used simplified features inspired by Maya designs. For example, repeating celestial symbols taken from carved Maya skybands form the iron railings encircling the second level of the museum building. The serpent body markings on Rosalila are mirrored in the grille work over the contiguous windows. Architect Angela Stassano wanted the serpent motif to convey the sense of its body embracing the viewer as it wraps around the museum.

One of the largest decorative painting jobs to be done was that of the museum's drop ceiling, which hovers above the Rosalila replica. Angela asked me to come up with a design for a painting on the vast white background, and Rudy suggested a celestial theme. I chose the figures from the carved bench of Copan's Structure 8N-66C, excavated by archaeologists from Pennsylvania State University in 1990, and the carved peccary skull from Tomb 1, found during a Peabody Museum expedition in 1892. At night, Moncho would set up a projector for me, and using projected slides of my drawings, I would trace the outlines on the still-unassembled ceiling panels to be painted the next day. I later learned that the workmen thought I had some incredible gift because it seemed that I arrived in the morning to a blank white surface and just started painting. They could not make out my fine pencil lines from the evening before and simply saw images appearing like magic from my brush.

Among others who helped with the ceiling painting was Luis Reina, an adept draftsman and sculpture cataloguer who had worked on the PAAC and other excavations. Luis learned every paint recipe for colors on the Rosalila replica and exhibits. He was also responsible for the acrobatic reassembly of the painted panels in the ceiling, for which he risked life and limb on shaky scaffolding that Michelangelo would probably never have set foot on. When the museum opened, IHAH named Luis the museum's manager.

The final painting of Rosalila and the other museum replicas took place in the last month before the museum's opening. To complete it in time, it required a cast not of thousands but at least of dozens. Sculptors Marcelino Valdés and Jacinto Ramírez and their Copaneco assistants all stayed many late hours to finish the job, together with Bill and me and our three sons. The students in the 1996 Harvard Summer Field School in Maya Archaeology painted too. Many of them stayed for an extra week on their own dime to help finish the job, racing ahead of the rain that would enter through the compluvium, working twelve hours a day, painting away to the booming accompaniment of Bob Marley (18).

At times it seemed incredible that with only perseverance and ingenuity, a strong dose of willpower, a few sections of scaffolding, some worn-down wheelbarrows, threadbare wood scraps, and one strong winch, we were able to erect all the exhibits in the museum and accomplish the job (19). In an interview about the museum videotaped in 2005, Angela Stassano reflected on the team spirit: "It is a source of great pride for everyone that the work was completed, that it was accomplished with the efforts of everyone working together. Especially, the people from the pueblo feel proud, and the workers, both those of the construction crew and the exhibition crew... because there were employees of all levels working in unison with top professionals, and that was beautiful because you do not often have the opportunity to bring together and foment that sort of unity." And throughout it all, we continued to be awed by what the Maya of Copan had accomplished 1,300 years before with nothing but stone age technology and people power.

Reconstructing Copan's Sculpture Mosaic

How does one go about reconstructing the sculptured façades fallen from Maya temples and palaces? Paying careful attention to the patterns in which the sculpture pieces fell from the buildings provides a wealth of information.

First excavation units are laid out, and the fallen pieces are drawn in their locations within the units. A catalogue number is assigned to each piece, and its number is recorded on the grid map before it is lifted. Later, we join the maps of all the excavation units into one large map of the entire structure or excavation. With this map, we can study the full distribution of the fallen sculpture.

Each numbered piece is drawn, photographed, and catalogued in a file and entered into the database at the Centro Regional de Investigaciones Arqueológicas (CRIA). We then separate them into motif groups, a main element or theme that is repeated on a building's façade. Motifs include things such as feathers, human figures, shields, masks, and plants. Data from the sculpture catalogue has been computerized in recent years for easier access, sorting of motifs, and recognition of building associations. Storage areas at CRIA are lined with shelves to keep the sculpture organized and out of harm's way.

Photographs and drawings are invaluable aids in reconstructing overall façades. Large quantities of sculpture require huge spaces and a lot of heavy lifting if they are spread out for analysis and refitting. Photo mosaics allow us to work on a tabletop or, now, on a computer with less cumbersome images. Ultimately, though, the refittings have to be checked against the actual pieces because shadows and other details in photographs can be misleading and result in false matches. When the motifs have been refitted, they are reassembled in a large sandbox that Bill Fash designed for this purpose.

At Copan, we are fortunate that the sculptors carved the details of the façade stones after they were in place on the building. In most cases, this allows us to determine exactly which stones were carved together. Commonly, buildings have identical motifs that repeat around them several times.Yet because of carving techniques, only one true set accurately matches its companion pieces.