Ancient scribes and sculptors left their marks indelibly on the city of Copan, not only on its public buildings and temples but also on private residences.

Based on documents recorded at the time of the Spanish conquest, scholars believe that the office of scribe was inherited, probably along noble lines. Scribal implements such as shell inkpots and ceramic paint pots found during excavations and represented on sculptures, as well as hieroglyphic inscriptions, inform researchers today about this specialized profession (164). A group of deities are the principal scribal gods, including Itzamna (God N), the Monkey Scribes, and Pawhatuuns.

Less is known of sculptors than of scribes, but the talents of many skilled sculptors were obviously required for Copan to have grown to such grandeur. Using jadeite axes, sharpened bone tools, and obsidian points, they worked the volcanic tuff into fluid, three-dimensional forms. The ancient Maya believed that sculptures embodied the supernatural forces they were carved to represent, so they sometimes ritually buried or destroyed carvings in order to dispel their powers. At some Maya sites, sculptors carved their names into their monuments, but those at Copan did not. Alongside the artistic sculptors worked many architectural stone carvers, together creating the animated architectural façades and freestanding monuments that make Copan so special.

Particularly revealing about scribes and other high-ranking members of Copan society are sculptures unearthed in a part of Copan called Las Sepulturas (165). This large residential area lies roughly one-half mile (1 kilometer) due east of the Principal Group along a bend in the Copan River. Before 1977, little was known about the area except that some tombs had been observed there-hence the local name, meaning “the sepulchers.”

Exhibit 44: Group 9M-18, Structure 9M-146

In 1977, as part of Gordon Willey's Harvard project, his team excavated a building at Las Sepulturas belonging to Group 9M-18. Earlier, Willey and Richard Leventhal had created a typology of four house group sizes for the Copan Valley. In order to learn about people and activities outside the Principal Group, they chose to investigate Structure 9M-146, a type 3 site, their third largest category. The archaeologists had no expectation of finding elaborate inscriptions at a type 3 site, but in Structure 9M-158 they discovered a beautifully carved hieroglyphic bench - now often called the "Harvard bench" - the first of its kind to be scientifically excavated outside the Principal Group. The bench discovery led to a reevaluation of the role of noble families in the social and political structure of ancient Copan and paved the way for further investigations into the lives and history of the people who supported the city's rulers.

Exhibit 42: Group 9N-8, Structure 9N-82

In 1978, during the first phase of the Proyecto Arqueológico Copán (PAC I), Bill Fash dug a test pit in the central plaza of Group 9N-8 in Las Sepulturas that revealed a stratigraphic sequence dating all the way back to the Preclassic period (1500 B.C.-A.D.250). In the 1980s, during the second phase of the project, William Sanders and his team undertook extensive excavations there. Bill expanded his plaza excavations and uncovered a platform, a living surface, and burials rich with jade and Preclassic pottery (now displayed in the Copan Regional Museum of Archaeology) dating to 100 B.C.

Meanwhile, David Webster and Eliot Abrams cleared the front and interior of the main building on this plaza, Structure 9N-82, discovering a huge array of sculptural fragments and an elaborate interior sleeping bench much like the one from Structure 9M-146 (166). The front of the bench was carved with a full-figure inscription dating it to the reign of Ruler 16. The bench has been on display in the Copan Regional Museum of Archaeology for many years. Subsequent analyses of the sculpture and artifacts from Group 9N-8 have provided scholars with new material for understanding the sociopolitical structure and daily life of Copan's supporting population in relation to the ruling establishment.

Structure 9N-82 became the largest structure systematically excavated outside of the Principal Group at Copan. Known popularly as the Scribe's Palace and the House of the Bacabs, it was the building where the methods of sculpture analysis were first devised that gave birth to the Copan Mosaics Project four years later. The PAC II investigators plotted the position of every block fallen from the building's sculptured façade. At first, working at the front of the building, Webster and Abrams marked the sculpture blocks as points inside grid squares. They numbered the pieces and then removed them all to the laboratory. When completing the excavations at the back, or south side, of Structure 9N-82, Bill refined the methodology. There he drew each piece fully on a grid map so that the relationships between the fallen pieces were clear and easy to reconstruct. Significantly, he excavated three figures from the upper register of the façade whose pieces had fallen into discrete groups, making possible a more accurate sculpture reconstruction than ever before attempted. He set the pieces face up in a large sandbox he designed, positioning them as they must have been on the masonry façade. His refinements of sculpture recording during excavation and analysis paved the way for all future façade sculpture work at Copan (see sidebar, p.10).

On the lower register of the front of Structure 9N-82, we reconstructed the carved scribal figures that gave the building one of its popular names, the Scribe's Palace.The scribal figures emerge from serpent-framed niches on either side of the doorway (167). The split serpent heads, with some centipede characteristics, formed the opening maw or portal to the underworld and were united by an elongated element with beads. They sit above a T-shaped element that has the meaning "na," or house. More recently, it has been suggested that this icon can be read as the house's ancient name, Noh Chapaat Nah. Each scribe figure wore a beaded water-lily pectoral and had outstretched hands, one holding a shell paint pot, and the other a stylus for writing or painting - the characteristic tools of the scribe.

Sadly, the heads of the scribe figures are missing, but an earlier carved scribal figure gives an idea of how they might have appeared. It also suggests the building's other common name, House of the Bacabs. Excavations in the fill of an earlier portion of Structure 9N82 uncovered the carved body of a seated human figure and, some distance away, its broken head. This charming figure, carved fully in the round, is that of a dwarf or the Monkey Scribe depicted in Maya art and legends (see 164). He, too, wears a water-lily pectoral and holds a shell paint pot and stylus, suggesting that he represented the patron of scribes. His netted headdress and the cave dripwater clusters on his shoulders suggest a reading of pawa (net) and tuun (dripwater stone), or pawahtun. Pawahtun are the old-man figures of the underworld who support the surface of the earth rather than the sky, as their counterparts the bacab do. In coining the name "House of the Bacabs," David Webster chose the more generic term bacab to describe the supporting figures. The Pawahtun also carry characteristics of the old deity Itzamnaaj, who invented writing.

When the scribe figure was buried, perhaps after the actual scribe who lived in the house died, new versions of the scribal patron were carved and placed in the doorway niches for the building's next phase or refurbishment. If the tradition of scribal functions passed to the next generation, then logically the next scribe would have designed his new façade to honor his scribal ancestors and patron deity.

The niches and figures just described adorned the lower register of the Scribe's Palace façade. Carvings on the upper register repeated the scribal themes. As is true of most buildings at Copan, all the upper-register sculpture mosaics became dislodged and fell from their original wall positions in ancient times. But analysis of the identified pieces from Structure 9N-82 showed that the configurations on the front and back façades were mirror images of each other, a common feature of Copan buildings. The front and back each displayed three human figures seated above "na" signs. They are believed to be depictions of actual people because their costumes show no supernatural attributes. Two other figures faced east and west, making a total of eight for the entire upper register of the building.

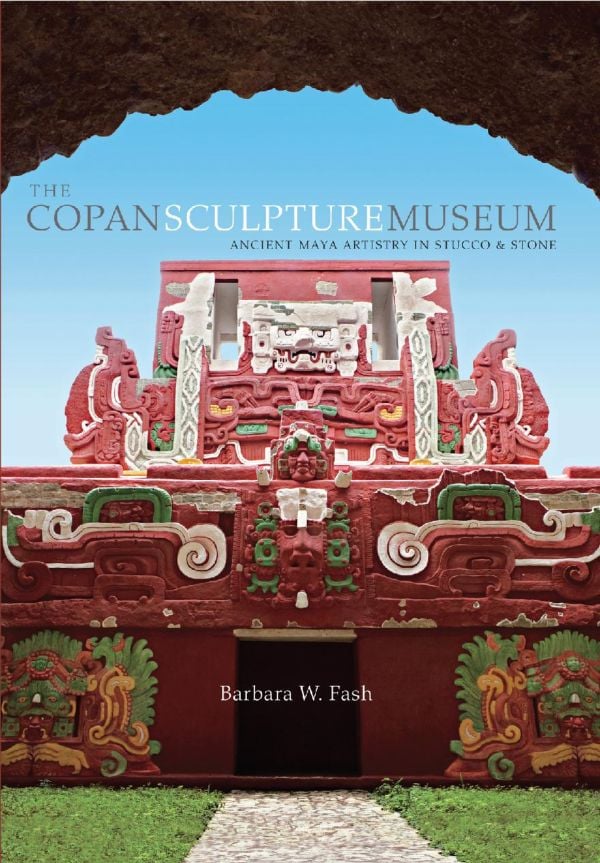

The front, or north, façade of the Scribe's Palace is reconstructed as exhibit 42 in the Copan Sculpture Museum (168). On the upper register, the central figure sits above his "na" sign in a position of royal ease within a recessed niche. These attributes emphasize his high rank, in contrast to the more exposed attendant figures at either side, who sit cross-legged. In his outstretched hands, this central figure most likely held a shell inkpot and a stylus. He wears a headdress consisting of a water lily tied above a reptilian mask, with a magnificent splay of feathers draping outward. The beaded water-lily symbol that the pawahtun on the lower register wear as pendants can be seen upturned at the top of the upper figure's headdress. A thick jade bar pectoral overhanging a heavy beaded collar is carved on the personage's chest.

A burial found directly in front of Structure 9N-82 held the remains of a male who wore a large rectangular jade pectoral as part of his attire. Bill proposed that this was the person portrayed as the central figure on the building's façade, an ancestor who is also mentioned in the inscription on the hieroglyphic bench from the interior room of Structure 9N-82, found by Webster and Abrams.

The attendants who sit on either side of the central figure gesture upward with their hands. In contrast to the higher-ranking person with his pectoral, the attendants wear only beaded collars. Their reptilian headdress masks are similar to the one worn by the central figure, but each is topped by a maize cob instead of a water lily.

The central figure on the back of the building was seated similarly above a na sign, and what little remains of his headdress indicates that it was another water-lily headdress. His attendants wore maize headdresses like their counterparts on the front, making a total of four figures with this headdress. The headdresses of the east and west-facing figures, on either end of the building, are poorly represented, but two large k'in or day signs are associated with them.

I suggest that the water-lily and maize headdresses worn by the seated figures on this building indicate the existence of two operational or corporate groups. One, represented by maize, was organized along kinship lines and landholdings, and the other, represented by the water lily, was a water group formed by the union of several kin groups who shared the same water source. Ethnographic accounts record the existence of these two types of corporate groups in both Chiapas and Yucatán. The water groups would have managed the hydraulic aspects of everyday life in their residential sectors. This hypothesis would explain the prominence of the central water-lily figure on this structure's façade. In 1994, Karla Davis-Salazar conducted excavations to the west of this plaza group and found the remains of an ancient reservoir.The central figure on the facade of Structure 9N-82 may have held important scribal duties in conjunction with the office of water manager.

Investigations of the Scribe's Palace and other portions of Las Sepulturas have yielded a bounty of architectural, hieroglyphic, iconographic, and artifactual data to aid in understanding the religious, social, and political lives of the Late Classic inhabitants of Copan. Together, these lines of evidence paint an increasingly clear picture of the way the larger residential areas operated. Scribes, sculptors, and no doubt residents occupying many other roles and professions gained prestige and economic power over time. Their authority within the social and political hierarchy perhaps eventually rivaled that of the ruler.