Copan has long been esteemed for the spectacular, freestanding stone statues, or stelae, that grace its ruins.

The first European explorers in 1576 marveled at the Copan sculptors' artistic creativity and their skill at carving in the round, which was unparalleled at any other Maya site. Gustav Strømsvik, who re-erected many of the fallen stelae in the 1930s and 1940s for the Carnegie Institution of Washington, called them the "crowning glory of Copan" (53, 54). The Copan Sculpture Museum displays three of the site's original stelae: Stela P (exhibit 3), Stela 2 (exhibit 9), and Stela A (exhibit 15).

The Latin word stela (plural stelae), from the Greek stêlê, describes a shaft-like stone monument set upright in the ground. David Stuart has deciphered the ancient Maya name for a stela in the hieroglyphs as lakamtuun, or "great stone." An earlier reading of the glyph, which has been discarded, was te' tun, translated as "stone tree." Epigraphers were initially intrigued by the word local people today use to refer to such monuments in Copan, te tun te, which Stuart believes is a modified form of the Nahuatl word for stone, tetontli. The modern word, however, does not correspond to the phonetic signs in the ancient Maya glyphs (55).

The freestanding stelae at Copan inspired the artist Frederick Catherwood to record them in meticulous drawings in 1839, which helped set the art of the New World on equal footing with that of ancient Egypt and the Ottoman Empire. The English explorer Alfred P. Maudslay devised the system of number and letter designations for the stelae and altars that is still in use today (although it was later amended by Sylvanus Morley), and he took some of the most valuable and artful photographs of the stelae during his early exploration of the site. Plaster casts of the stelae made at the turn of the twentieth century were shipped to world's fairs and early museums for display. Many still stand in museum exhibition halls around the world, preserving details often eroded on the originals.

It was the Copan sculptors' good fortune to have soft, workable volcanic tuff as a medium in which to express their virtuosity at carving. Sculptors are known to have inscribed their names and titles on stone monuments at a few other Maya sites, but the practice was not followed at Copan. Stylistic clues hint at the hand of one sculptor or another, but it is likely that many people worked on a monument in concert under a single master. Each stela was carved from one huge block of tuff quarried from one of the outcrops in the hills nearby. Once hewn from the outcrop, the monolith was probably rolled on logs to the spot where it was to be erected.

Each stela was given a long, smooth tang, about half again the length of the carved portion, that secured it upright in the ground. A hole was dug and formed into an offertory cache box, usually cruciform, and a supporting base of large stone slabs was laid on the ground surface, securing the underground shaft. In this vault, people placed offerings such as pottery vessels, shells, jade beads, and stalactites. Then the monolith, still uncarved, was lowered into the hole and offering box using ropes and wooden scaffolds. The act of erecting the stela was conceived of as an act of planting (ts'ahp).Hieroglyphs on three stelae at Copan, including Stela A in the museum, record the event using the phrase "ts'ahpaj lakamtuun," meaning "the great stone was planted."

Workers probably built a temporary roof over the stone to keep it moist for easier carving. Once the carving was completed, the stela was painted red using an iron ore or cinnabar pigment. Many stelae, such as Stela P and 2 in the museum, Stela C at the archaeological site, and Stela 12 in the foothills overlooking Copan, still show traces of red paint.

For many years, researchers speculated about whether the figures carved on stelae at Maya sites represented deities or historical personages. In 1961, Tatiana Proskouriakoff identified the names of Maya rulers in stelae inscriptions at the site of Piedras Negras on the Guatemala-Mexico border. Since then, researchers have widely accepted that the figures on Maya monuments are portraits of the semi-divine rulers who held sway over the cities' fortunes.

Names and historic events recorded in the hieroglyphs on stelae and on some altars give us dynastic sequences and events linked to rulers' reigns for many lowland Maya sites, including Copan. Some rulers, and in rare instances deities, are named as the "owners" of stelae in the inscriptions. Today, twenty-four stelae stand in the Copan Valley, and another 39 broken and fragmented ones are kept in storage or in the Copan Regional Museum of Archaeology for safekeeping. Most of the fractured stelae were early monuments that were buried under later architecture. Several have come to light through archaeologists' tunnel excavations into the pyramidal bases of major structures.

Before the long reign of Ruler 11, K'ahk' Uti' Chan, from A.D. 578 to 628, it was customary to destroy and bury one's predecessor's monuments. K'ahk' Uti' Chan and his successors, K'ahk' Uti' Ha' K'awiil and Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil, broke with this tradition. They not only left their ancestors' monuments intact but sometimes even built around them.

The rulers of Copan often erected stelae to mark the completion of a time period in the cyclical Maya calendar. The stelae's inscriptions, however, usually start with a date in the linear Long Count reckoning, which anchors the cyclical dates in absolute time.

Throughout the Classic period, rulers erected and dedicated monuments every k'atun, a period equivalent to 20 years, and occasionally at subdivisions of the k'atun, the lahuntun (10 years) and the hotun (5 years). The ruler's semi-divinity was recognized in the carved texts through the title ajaw (lord), which signaled his transformation into the embodiment of sacred time. Astronomical events are also important parts of the texts on stelae and may refer to the ruler's spiritual journey into the supernatural world, a privilege restricted to rulers as semi-divine beings.

Most of the rulers portrayed on stelae at Copan carry in their arms a double-headed serpent, which, by the Late Classic period, became stylized into a rigid bar. The serpents' mouths are opened wide to show emerging heads, representing the act of conjuring a deified being back into this world. Sacrificial offerings and bloodletting, generally from a person's ear, tongue, or penis, using sharp instruments such as thorns and stingray spines, were often parts of these conjuring rituals, a means of feeding the supernatural forces being called upon.In general, the serpents on stelae are death serpents, with fangs and fleshless mandibles.

The cruciform vaults over which stelae were usually erected at Copan symbolized the four directions and the four corners of the universe. The stela was placed where the four quarters of the vault met at the center of creation. The ruler portrayed on the stela embodied this sacred axis.

Sometimes, stelae inscribed with texts and figures depicting rulers were paired with freestanding altars, the focal points of rituals carried out by rulers and priests to dedicate the two monuments and honor the passage of time. Although no altar is displayed with its stela in the museum, they were the stones upon which to let blood, make sacrifices, and pour sacred liquids. Some altars and stelae are depicted, either on the altar itself or on ceramics and bones, as sacred time markers bound with tied knots, indicating that they were "bundled" - from the deciphered verb k'altun in the hieroglyphs, for the act of bundling. Sometimes the altars' proper names were inscribed on them, and these often included a reference to k'antuun, or "yellow/precious stone." Altars also recorded calendrical events and named personages. Sixteen stelae at Copan have associated altars, but most altars were carved as stand-alone monuments unrelated to a stela. These are often much smaller than those directly associated with stelae. Although much iconographic study remains to be carried out, Late Classic altars paired with stelae tend to depict supernatural beings that were perhaps particular to rituals involving the altars. Earlier altars often display a continuation of the stela's hieroglyphic text. Altars have been found purposely broken and cached under stelae or reused in architecture. Claude Baudez noted that in the eighth century, altars carved with complex scenes and hieroglyphic texts took on an importance nearly equal to that of stelae.

In 1920, Sylvanus Morley classified the stelae known at Copan into three categories based on their design layout: hieroglyphic inscriptions on all four sides, inscriptions on three sides with a figure on the fourth, and inscriptions on two opposite sides with back-to-back figural representations on the other two. Later researchers identified additional design arrangements, including inscriptions on three sides with the fourth left plain, two profile figures on opposite sides with no text, and a figure wrapped around three sides, with the fourth side inscribed in hieroglyphs. The most common stela presentation is Morley's second category, inscriptions on three sides with a figure on the fourth. The three stelae displayed in the Copan Sculpture Museum all fall into this category.

Scholars such as Herbert Spinden, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, and Miguel Covarrubias also classified the Copan stelae, using not just style but also chronology as a criterion. They determined that the earliest, or archaic, monuments were carved in low relief and were purely textual. Over time, artists began to carve stelae in slightly higher relief and to portray human figures on them. Stela P in the museum is a good example. The stylistic sequence ends with ornate Late Classic monuments displaying fine carving in extremely high relief. These categories are useful for stylistic dating and have been supported by the hieroglyphic dates on the monuments. When excavators find only partial monuments lacking inscribed dates, stylistic dating is a means of retrieving the otherwise lost chronology.

Influence from the Maya of the Guatemalan highlands and from lowland sites such as Tikal in the Petén helped shape the creative styles of the early Copan monuments. Brief inscriptions and portrayals of rulers in profile eventually gave way to Copan's lengthy texts and frontal poses. Studies indicate that the high-relief carving of the Late Classic period, which has become a hallmark for Copan stelae, evolved first on the city's elaborate temple façades. Designs on temple façades were already shifting from modeled stucco to stone carved in high relief by the end of the Early Classic period, or the seventh century, but stelae sculptors preferred more archaic styles into the eighth century.

Rulers are generally portrayed on the stelae as larger than life and heavily costumed. Elaborate headdresses with attached earflares, heavy belts with loincloths, and ornate sandals make up principal parts of the compositions. Epigraphers have deciphered names for parts of the costumes, such as tuup, earspool, and sak huun, white headband. Later monuments, such as Stela N at the Copan ruins, show smaller figures and animals weaving in and out of the relief alongside the ruler. These may be ancestors, animal spirit companions, or mythical spirits in the supernatural world. Some of these additional figures are carved in extremely high relief, with cutaway areas giving a lighter, airier quality to the monument.

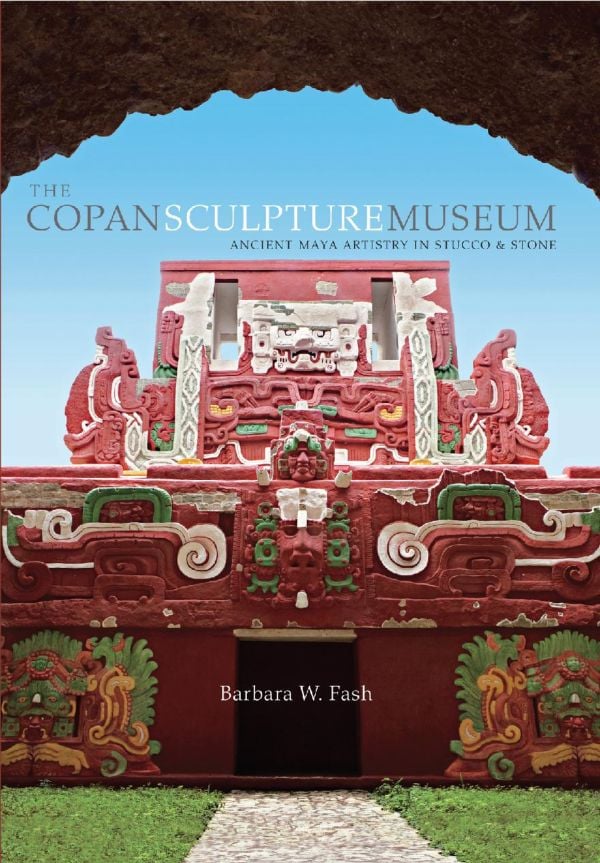

Originally, four stelae were chosen to be displayed in the Copan Sculpture Museum, representing a chronological sequence of earlier to later rulers. Stela N, one of the few monuments still standing when John Lloyd Stephens visited the site in 1839, was selected to represent the latest monument. However, because of its high relief and cutout forms, it proved too challenging to replicate and was never moved into the museum. Still, the three stelae on display—Stelae P, 2, and A—allow visitors to trace the changing surface treatment and style of the monuments. These are some of the finest examples of their highlighting the reigns of three important and long-lived rulers.

Exhibit 3: Stela P

Stela P is a monument erected by Ruler 11 to glorify himself as well as to honor K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', the founder of his dynasty. Ruler 11's name is phonetically read as K'ahk' Uti' Chan - Fiery Sky or Fiery Snake. It is written using glyphs for smoke followed by a sign for either sky or snake, which are homophones in Mayan. K'ahk' Uti' Chan was born in A.D. 563, became king in 578, and died in 628 at the age of 65. The stela was dedicated on 9.9.10.0.0, 2 Ajaw 13 Pop, or March 21, 623 - the end of a lahuntun, a 10-year period when the Rosalila temple was still in use. Archaeologists believe that Stela P was originally erected in another nearby location, closer to Rosalila, and was relocated to a spot slightly northwest of Structure 16 in the eighth century when the building's expansion necessitated its repositioning.

Stela P is one of the finest examples of the Early Classic style at Copan, a style that can be seen on several other early monuments at the site, including Stela 7, also erected by Ruler 11, and Stelae E and 2, raised by Ruler 12. The monument is wider at the top than at the bottom. Three of its sides are covered with glyphs, and its front portrays K'ahk' Uti' Chan holding a two-headed serpent over his chest. The serpent's curving body, which looks natural and flexible on this and other early stelae and on later ones becomes a bar, is often referred to as a ceremonial bar. From the open mouths of the serpent heads in profile emerge two human faces, also in profile. It has been suggested that they represent the old "paddler gods," a mythical pair who paddled a canoe through the underworld to the place of creation. They seem to personify the sun on its daily journey. On the back of the stela is a rare hieroglyph naming the ceremonial bar; it is a small version of the figural carving showing the two serpent heads back to back.

The ruler wears a jaguar pelt skirt with a loincloth draped over it and a heavily decorated ceremonial belt. Jade pendants dangle from twisted fabric, and youthful masks hang on the ruler's chest between the heads of the serpent bar and on the loincloth. A squirming serpent body with an eroded head can be seen alongside the ruler's legs on either side.

The jaguar pelt repeats in the upper background, perhaps representing the night sky. The Classic Maya and people of other cultures in ancient Mesoamerica believed that upon setting, the sun entered an underworld teeming with fierce jaguars and other creatures, and the stars in the night sky were like the spots on a jaguar's pelt. The ruler's ornate bird headdress is similar to that on the sun god on Rosalila; note that the beak is missing and would have been inserted into the extant cavity. A few objects from the Maya area that share many of the features of this headdress are clay incensarios, or containers for burning incense offerings, from Copan's sister city of Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico, and stucco masks from the site of Kohunlich, Belize. If this is the same sun god headdress associated with K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' on Rosalila, then Ruler 11 might be dressed for a ceremony in which he portrayed both the sun god and the founding ruler. Some scholars believe this is a posthumous portrait of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' himself.

Exhibit 9: Stela 2

Stela 2, dedicated only 29 years after Stela P, bears a striking resemblance to its predecessor. Both are carved in the conservative low Eks relief of their time, with hieroglyphs on three sides and a figure on the fourth. Although Stela 2 is shorter and wider than Stela P, the two are closely paired in symbolism. The ruler portrayed on Stela 2 has been identified as Ruler 12, K'ahk' Uti' Ha' K'awiil. Like Ruler 11 on Stela P, he is dressed in ritual attire to celebrate an important period ending in the calendrical cycle, in this case 9.11.0.0.0, or A.D. 652.It seems likely that the similarities between the two stelae were intentional, emphasizing that Ruler 12 is being compared to his predecessor on Stela P, with both performing period-ending rituals.

Ruler 12's elaborate costume helps us understand aspects of the ritual being commemorated. Like Ruler 11, he is shown holding a flexible, two-headed serpent. Out of the serpent's mouths emerge the heads of deities, identified as the jaguar solar deity (also known as the old "jaguar paddler"). The ruler wears sandals and a kilt and headdress made of spotted jaguar skin, appropriate ritual attire for bringing the jaguar solar deity to life again. He also wears a jaguar helmet (a departure from Ruler 11's bird helmet on Stela P) and two smaller masks with jaguar characteristics, one above the main helmet and the other below his chin. The square earflares, profile serpent heads, and braided cloth are other standard features of Maya rulers' headdresses. Vegetation sprouts from the upper headdress, and a curious hand emerges from a flower-like petal. These may be aquatic plants because the jaguar is affiliated with watery realms.

Stelae 2 also depicts the elaborate loincloth and belt, dangling polished celts, and shell tinklers that rulers wore to their ceremonies. Although eroded here, small, youthful masks appear on Ruler 12's belt and his chest. In the background, snakes spiral from his elbow shields. Like Stela P, Stela 2 appears to have been moved from its original location later in Copan's history. It was reset over a cruciform chamber in a platform overlooking the ballcourt, and the date of the platform is several k'atun later than the stela's dedication date. Initially, members of the Peabody Museum expedition in the late 1800s found the stela in two pieces on the ballcourt floor and set it up there. Later, the Carnegie expedition discovered the cruciform chamber in the platform and re-erected the stela on that spot.

Exhibit 15: Stela A

Stela A is possibly the most popular monolith at Copan today because of its beautiful, high-relief carving and the fact that it is one of the few monuments with a preserved face. Serene Maya features were a trademark of Copan sculptors, especially during the reign of Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil, Ruler 13, from A.D. 695 to 738. The stela's dedication date is 9.14.19.8.0, 12 Ajaw 8 Kumk'u, or A.D. 731. Waxaklajun Ubaah K’awiil erected Stela A three winals (sixty days) after Stela H and directly across the Great Plaza. The text on Stela A uncharacteristically repeats some events also recorded on Stela H; these involve using sacred relics to recall deceased ancestors from the otherworld. Sometime in the nineteenth century, a traveler to Copan carved the name "J.Higgins" into the border framing the glyphs on the backside. Despite this person's attempt to be immortalized, no one today has the slightest idea who the graffitist was. Stela A was erected over a cruciform chamber to the north of Structure 4 in the Great Plaza. Strømsvik, who excavated the chamber, found it to contain pottery fragments, stalactites, and stone flakes. The hieroglyphic text on the stela mentions that the dedication offering took place in the Great Plaza. The altar in front of Stela A was also placed on the central axis of Structure 4, which highlights the importance of the altar and its offerings as the focus of the dedication ceremony, under the gaze of the ruler himself, carved in stone for eternity.

It is generally agreed that the figure carved on the front of Stela A is Waxaklajun Ubaah K'awiil. His name is mentioned in the text on the monument, followed by the emblem sign for Copan, with its signature bat head.The emblem glyphs designating three other kingdoms, Tikal, Palenque, and Calakmul, appear on the south side of the monument (66). These three, along with Copan, are believed to have been the four capitals of the lowland Maya world at the time. Each emblem glyph is paired with one of the four directional glyphs – those for north (xaman), south (nojool), east (lak'in), and west (chik'in) – emphasizing the four-sidedness of the Maya worldview. New interpretations suggest that the emblem glyphs may refer to rulers or nobles from those cities who were visitors to Copan.